Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Maj. Megan McClung and Capt. Travis Patriquin, RIP

December 11, 2006 · Michael Fumento · Michael Marks.</p> · WeblogI only heard Marine Major Megan McClung yell once, but it was righteous anger. If this were fiction, it might be considered foreshadowing. It was at Camp Ramadi headquarters outside of the city proper and away from the hostilities. The 34-year-old McClung, head Public Affairs Officer (PAO) for Al Anbar Province, was barking at a public affairs sergeant. "Ramadi is the most dangerous city in Iraq and you're going to get your men out there to cover it!"

This was in October and the previous spring I had been angry with McClung, though I'm glad I didn't tell her. She was a captain then with her headquarters at Camp Fallujah. I had made it clear I wanted to spend my entire embed in Ramadi because that's where the action was and because on my first Iraq trip a year earlier I had seen Fallujah but been denied Ramadi when I wound up "embedded" on a surgical bed in Baghdad. Yet when I returned this spring to Baghdad to renew my press credentials and expected to fly straight from there to Ramadi, I was dumbfounded that McClung had routed me right back to Fallujah and its environs. When I saw her in person, she explained that she wanted me to spend time with Military Transition Teams (MiTTs) in the area to see how well their training of the Iraqi Army was progressing.

It was a prescient move on her part, especially considering that a tremendous increase in MiTT teams embedded in indigenous units has become a major part of all plans to ultimately turn the war over to the Iraqis. In any case, the trip did end in Ramadi where during just a few short days I saw and reported on more combat, more courage, and more camaraderie than you might see elsewhere in Iraq in a year.

For my last embed, I was in Ramadi the whole time. But again McClung guided me so I saw what I needed to see rather than what I thought I needed to see. After each embed she diligently provided information that I'd been unable to gather in the field. I have two dozen emails from her on my computer, the last dated November 30. The lady I once begrudged I grew to have great respect for.

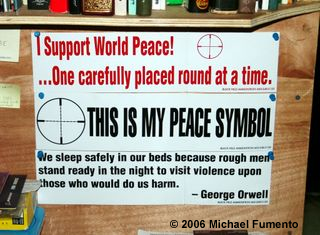

Capt. Patriquin's famous desk

Capt. Patriquin's famous desk

I also developed that respect for 32-year-old Captain Travis Patriquin of the Army's First Armored Division. (McClung was with the First Marine Division.) I photographed Patriquin's desk, which was covered with bumper stickers such as George Orwell's observation that "We sleep safely in our beds because rough men stand ready in the night to visit violence upon those who would do us harm." When I published my photo set from the trip, that desk quickly became a blogosphere celebrity.

Patriquin was exactly the sort of officer we need in Iraq. He spoke at least five languages including fluent Arabic, and was a major player in getting Ramadi sheiks to start supporting Coalition operations by sending men into the Iraqi Police and urging civilians to expose al Qaeda terrorists. He fought in one of the fiercest battles of the Afghanistan war, Operation Anaconda, later receiving the Bronze Star. Patriquin also provided a terrific inbriefing, giving an overview of a city that seems slowly to be improving but is still too much like the local graffiti states: "The graveyard of the Americans." I quoted him at great length in my major article about the trip in the Nov. 27 Weekly Standard.

While most journalists heading into Ramadi require no PAO escort, for some reason on December 6 both McClung and Patriquin, plus 22-year-old Army Specialist Vincent J. Pomante III decided to jump into a Humvee to accompany Oliver North and his crew from Fox plus some journalists from Newsweek downtown. A tremendous blast from an improvised explosive device (IED) ripped apart their truck, killing all three. Mercifully, it appears all died instantly. I heard about Patriquin his cousin, then left a message for McClung asking for verification and offering her my condolences. Then I found out about her. McClung has the dubious honor of being the first female Marine officer and highest-ranked female officer overall killed in the war.

Why, people who have never been to war ask me, do I actually like being in a combat zone? Partly it's the feeling of being responsible for the lives of everyone else and they for you. Partly it's that you never feel more alive than when you know you're so close to death. You develop the bond that Shakespeare marvelously described as a "Band of Brothers." And when you leave the killing fields behind, that bond remains and is something that nobody who hasn't experienced it will ever appreciate. You accept that some brothers will die, but that doesn't make it easier when it happens.

Given the season, it seems appropriate to quote from Michael Marks's haunting poem, "A Soldier's Christmas:"

"But isn't there something I can do, at the least,

Give you money," I asked, "or prepare you a feast?

It seems all too little for all that you've done,

For being away from your wife and your son."

Then his eye welled a tear that held no regret,

"Just tell us you love us, and never forget.

To fight for our rights back at home while we're gone,

To stand your own watch, no matter how long.

For when we come home, either standing or dead,

To know you remember we fought and we bled.

Is payment enough, and with that we will trust,

That we mattered to you as you mattered to us."

Note: This blog will be updated as more information becomes available. "A Soldier's Christmas is copyright 2000 by Michael Marks.