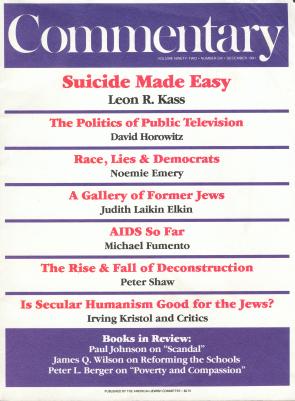

Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Writer Michael Fumento investigates: "AIDS So Far."

December 01, 1991 · Michael Fumento · Commentary Magazine · Aids

One of the last books published on AIDS in 1990 bore the ominous title, The AIDS Disaster. It called for massive spending, at a level the authors admitted would guarantee a great deal of waste, to contain an epidemic growing by leaps and bounds.

Yet if anything is clear one decade into the AIDS crisis, it is that the estimates and projections about the epidemic have proved completely wrong.

To be sure, some of those projections were the work of non-authorities, such as Oprah Winfrey’s prediction that one-fifth of all heterosexuals would be "dead of AIDS" by 1990, or Gene Antonio’s assertion in The AIDS Cover-Up? (with claimed sales of 300,000) that by the same year there would be as many as 64 million people in the U.S. infected with HIV. But the more "responsible" estimates were almost as scary.

In 1987, in its first cover story on AIDS, which featured the faces of a white man and woman in business dress, U.S. News & World Report informed its readers that "The disease of them suddenly is the disease of us . . . a plague of the mainstream, finding fertile growth among heterosexuals." The article stated:

By 1991, according to the most conservative estimates, 270,000 people will have been stricken, 179,000 will have died — and new cases involving heterosexuals will have multiplied tenfold to 23,000. Almost 4,000 babies will have contracted the disease by being exposed to the virus while in their mothers’ wombs. The Centers for Disease Control [CDC] estimates that 1.5 million Americans now carry the virus but display no symptoms. Others think that number may be as high as four million.

By 1989, the news was worse. The U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) projected from 300,000 to 480,000 cases of AIDS in the country by the end of 1991; Surgeon General C. Everett Koop quickly embraced the GAO figure.

International estimates and projections were also horrific. In 1986 the World Health Organization (WHO) predicted as many as 100 million worldwide infections by 1990. While most infections were to be in third-world countries, the West, even aside from the United States, also be hard hit.

The British Royal College of Nursing predicted that "A million people in Britain — one in fifty — will have AIDS in six years [1991] unless the killer disease is checked."

We are now in the last quarter of the year 1991. How does the epidemic match what U.S. News dubbed the "most conservative estimates?" As of the end of August, 188,348 cases had been reported in the United States, of which 121,196 had ended in death. Heterosexual cases, including among Haitians and Africans, came to 10,279, and 2,696 babies had been diagnosed as having contracted AIDS through their mothers. A mere 727 whites, middle-class or otherwise, are listed as having gotten the through heterosexual contact — less than one half of 1 percent of the total caseload. The current CDC estimate for infections since the epidemic began is one million, which includes the almost 187,000 reported cases.

Thus, the figure of 1.5 million carriers that "may be as high as four million" turns out to have been closer to 800,000, while the actual AIDS cases, even when all 1991 cases have been reported, will be many fewer than CDC estimate of 270,000, not to mention the GAO estimate of 300,000 to 480,000.

Elsewhere in the world as well, the epidemic has proved considerably less ferocious than expected. Only slightly more than 4,000 cases have been reported in all of the UK in the course of ten years of the epidemic. As to the fearsome WHO projection, by 1990 it had been scaled down from 100 million to 8-10 million, but even this figure grossly inflated, in that it stipulated for North America alone one infection per 75 males, at least twice too high.

Not nearly so many people will get AIDS and die, then, as the CDC any others had predicted. This much is acknowledged. But how has the good news been received?

As one might expect, those who have been proved wrong have downplayed the importance of the figures and/or come up with far-fetched excuses for their mistakes. In general, the miscalculation has been attributed to "safer sex," meaning abstinence, the use of condoms, or other risk-reduction behavior, or to "new developments," meaning drug therapy involving the use of AZT or inhaled pentamidine (to stave off a particular AIDS-associated pneumonia).

Thus, Dr. Sten Vermund, chief of the epidemiology branch of the division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases: "We have seen what we had always hoped we would see: some kind of measurable public-health benefit from the huge investments that we are making."

The new-developments theory has generally been accepted by the media, and will probably stick. To quote Elizabeth Whelan of the American Council on Science and Health, "It is widely known and accepted that the leveling off in new AIDS cases among homosexual men ... was the direct result of therapy with AZT." (Whelan, not coincidentally, is one whose projections for the AIDS epidemic have proved far exaggerated.) But in fact AZT did not play a significant role, and there has been no tangible result from "these huge investments."

What happened was simple. From 1981 to 1982, diagnosed AIDS cases increased 264 percent. From 1982 to 1983, they increased 170 percent, then 103 percent to the next year. By 1986, the epidemic had slowed to a 63-percent increase from the year before. There is nothing mysterious in this; it is standard procedure for all epidemics, from the Black Death (bubonic plague) to polio to the flu. All epidemics follow a curve which is never linear, never truly exponential. Even as they grow larger they always grow more slowly, until eventually they level and drop off.

Data collected by the CDC and others indicate that HIV had done most of its dirty work by 1985 — the year of the first big media scare. Indeed, in some major U.S. cities the incidence of HIV infection had apparently leveled off in homosexual populations by 1982, and in all cities probably by 1984. Since infections begin manifesting themselves as AIDS cases in as little as two to three years (though the median incubation time is about eight to ten years), for the nation as a whole a sudden slowing in the case diagnosis rate would thus have shown up by 1987. And so it did.

Mitchell Gall of the National Cancer Institute, writing in the April 1990 Journal of Acquired Immunity Deficiency Syndromes (JAIDS), notes that reality was veering off from his own projected figures for the epidemic (and those of the CDC) by mid-1987. That happens to coincide nicely with the introduction of AZT, to whose prophylactic efficacy Gall credits the downturn.

In fact, however, it was not until September 1987 that the drug was available to persons who were not suffering the end-stage disease, that is, persons who could use it for prophylactic purposes, and it was not until mid-1989 that prescriptions for that purpose finally jumped.

Furthermore, in October 1989 it was reported that AZT proved effective in delaying onset of the full-blown disease in only one-third to one-half of all takers. In other words, even among the tiny number of men who may have been using AZT in 1987 for prophylactic purposes, fewer still were likely to be seeing any effect.

As for inhaled pentamidine, it was not even approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) until June 1989, although a very few hospitals had begun using it with some AIDS patients as early as 1987. In fact, for the year 1987, according to the CDC, only 7 percent of persons with HIV in a major study group were using any kind of drug.

Thus medical developments were far too little and far too late to have affected a disease curve already falling behind projections. This was confirmed by data presented in two different reports by the New York City Department of Health at last year’s AIDS conference in San Francisco. Among white males in New York City, AIDS deaths stabilized as early as 1985, with diagnoses among white male homosexuals stabilizing in 1986. One of the papers, by the city’s director of AIDS Research, Rand Stoneburner, explicitly challenged the AZT thesis.

Indeed, the Gall thesis contains within it the seeds of its own undoing. Gail asserts that one indicator of the efficacy of AZT prophylaxis is that while the rate of increase among homosexual males dropped off dramatically, intravenous drug abusers (IVDA’s) without access to AZT enjoyed no such downturn.

Alas, the yearly CDC figures released at about the same time as Gail’s article showed that while case reports from male homosexuals increased 8.4 percent over the previous year, non-homosexual IVDA cases increased only 5.1 percent.

Interestingly, for all the acknowledgment of the decline of the epidemic among homosexuals, it seems that nobody wants to talk about the almost equal decline among IVDA’s. Over and over again one hears, "Good progress has been made among homosexuals, but the rest of the epidemic continues out of control." Yet nothing could be further from the truth.

For one of the big secrets of the AIDS epidemic is that it is declining among all risk categories, a point made graphically in a chart in a recent issue of Science accompanying an article by Ronald Brookmeyer of Johns Hopkins University. The chart and the accompanying data are all the more interesting since Brookmeyer, like Gail, had previously greatly exaggerated the scope of the epidemic. The chart also shows a flattening of the epidemic long before any therapy was available that could possibly have delayed the diagnosis of full-blown AIDS.

(Note from the author: A complication here is the recent CDC announcement that as of January 1992 it will seek to expand the definition of AIDS to include anyone with HIV who has fewer than a certain number of the type of white blood cell which HIV destroys. The result, according to some epidemiologists, may be as much as a 50-percent jump in reported new cases, as people will be diagnosed with AIDS who have no life-threatening illnesses and in fact may have no disease symptoms whatsoever. Such a jump in reported cases, it bears stressing, will be a result riot of anything tire epidemic has done, but rather of what the government will have done. This seems to be yet another case of the CDC broadening the definition of the disease to make the epidemic look worse.)

Did any of this result, as homosexual groups and AIDS educators claim, from safer sex? Safe sex may have played a part with homosexual males; clearly, it has reduced the incidence of male rectal gonorrhea. And since it has also reduced the incidence of hepatitis-B infection in first-time male blood donors in those cities hit hardest by AIDS, it may vitally affect the number of cases in the post-epidemic years to come.

But with equal certainty safe sex has played no role among IVDA’s, who are getting the disease not from sex but from needle-sharing. Nevertheless, every year the IVDA and homosexual trends have roughly matched up. Giving safe sex the credit for the decline in new infections ignores the saturation effect which applies to all diseases-and which explains, for example, why in the 14th century one-half to two-thirds of all Europeans escaped the Black Death. This same saturation effect is now at work among IVDA’s and in the AIDS epidemic in general.

If it is now a matter of general agreement that the scale of the epidemic has been overstated, there is still some dispute over how soon an actual plateau will be reached. The main source of the disagreement lies in how one calculates the lag time for newly reported cases. And this is where the issue of heterosexual transmission comes in.

Thus, the statistician Peter Plumley, who believes the epidemic itself may have peaked in the third quarter of 1990, also finds that there is still "an upward trend" in the heterosexual portion of the epidemic — not surprising, since cases of heterosexual transmission represent later infections from already infected IVDA’s and homosexuals. Even so, says Plumley, it is a "slowing increase and perhaps a decrease in what continues to be a very small proportion of the epidemic" (emphasis in original).

Moreover, there is new evidence that many cases of allegedly heterosexual transmission are not that at all. This past April, the CDC undertook a special investigation of such cases in Florida, a state which has reported fewer than 9 percent of all U.S. adult AIDS cases but more than 15 percent of U.S. cases attributed to heterosexual contact.

Using medical records and personal interviews, the CDC found that a full 30 percent of these actually belonged in other risk categories. Of the remaining 70 percent, most were Haitians. Then there were those who could not be re-interviewed or who refused to be reinterviewed or who lied upon re-interview. That does not leave many native-born heterosexuals.

Since Florida’s classication procedures are no better and no worse than those of the other 49 states, it is safe to presume that the national statistics on heterosexual transmission, low as they are, are significantly overstated.

To the AIDS establishment, this is a particularly worrying development. Randy Shilts, the author of the best-selling AIDS book And the Band Played On, confessed in a recent interview, "The AIDS groups were successful in their propaganda effort, saying every heterosexual was about to get AIDS. But they weren’t. . . . And once the average heterosexual stopped feeling at profound risk, then the concern just went down to nothing."

Whether one accepts this explanation or not it is certainly true that coverage of AIDS at the more respectable newspapers has diminished, and what remains is of better quality. The New York Times’s reportage on the week-long international conference on AIDS this past spring in Florence, Italy, made but one mention of the possibility of a heterosexual epidemic. The Washington Post’s reporter never even alluded to it. One of the three major American newsmagazines ran nothing on the conference at all.

What, finally, of the future?

If the good news is that homosexuals have reduced their risk activity, the bad news is that, as the epidemic slows, they are beginning to relapse. The San Francisco Department of Health has found, for example, that a large percentage of young homosexual men have gone back to engaging in the riskiest of activities, anal sex without a condom. Similarly, in King County, Washington (which includes Seattle) there has been a sharp upturn in rectal gonorrhea in homosexual males.

The increase in risky homosexual behavior is not surprising in the light of the history of sexual diseases. By the early 1930’s, according to Allan Brandt in No Magic Bullet, approximately one out of every ten Americans suffered from syphilis; each year, U.S. citizens contracted almost half a million new infections. If it reached the nervous system, syphilis could cause insanity, paralysis, or blindness; it was also a leading cause of miscarriages, cogenital defects, and sterility. Yet people continued to engage in unprotected intercourse.

Just so, homosexuals will continue to have "unsafe sex" and intraveneous drug abusers will continue to share needles and there will continue to be new HIV infections and new AIDS cases. Perhaps 5,000 a year, perhaps 15,000; no one knows.

Only a highly effective vaccine would bring new AIDS infections to a level anywhere near zero, and that would take massive innoculations over a period of years. In the meantime, as the AIDS educators truly say, "Education is our only weapon."

But what the AIDS educators still have not acknowledged is that there is not a thing they or anyone else can do about individuals who insist on engaging in high-risk behavior, short of throwing them into guarded quarantine, a policy which is, of course, totally unacceptable. AIDS cannot be socially engineered out of existence; the best that can be done is to tell people exactly how the disease is transmitted and, especially, who is at greatest risk.

Yet this is precisely what the AIDS establishment, sacrificing scientific accuracy to political correctness, has so far tried desperately not to do. And in this area there is no sign of any change.

Only recently, a consortium of ad agencies announced that it is seeking $30 million in donated space and air time for advertisements targeted, as the Wall Street Journal put it, "at people who still think AIDS is someone else’s problem." Targeted, in other words, at white, middle-class heterosexuals. Here we go again.