Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Toyota Hysteria

March 02, 2010 · Michael Fumento · Independent Journalism Project · Transport  Car defects do occur, and can have catastrophic consequences.

Car defects do occur, and can have catastrophic consequences.

This was my Toyota MR2.

While driving with my future wife along California’s Highway 1 south of Big Sur, my new Toyota MR2 suddenly fishtailed. It shot off a cliff, then rolled 350 feet before stopping. Mary sustained a broken neck and crushed skull, but she made a miraculous recovery. I suffered only scratches and bruises. The pavement was dry, I was under the speed limit, and skid marks testified to my desperate effort to stop.

That was 1992. While Mary was still in the hospital, I discovered Toyota was replacing the model because, according to one car magazine, expert drivers reported that it suffered “radical, often terminal oversteer.” The model was never recalled, but it was quickly replaced. We settled out of court, with Toyota making no admission of liability.

You might think I’d be prejudiced against Toyotas after that. But I’m not. I later bought another one, and my wife owns one now. But what I am worried about, with the current avalanche of unintended-acceleration complaints against the company and the congressional hearings, is the hysteria promoted by sensationalist headlines and pompous government officials.

Every accidental death is a tragedy. But the imagery of Toyotas running amok like something out of a Stephen King novel is simply false. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration frequently receives “speed control” complaints; a recent New York Times analysis found the agency received almost 13,000 over the last decade.

Yes, that analysis found that Toyota had the second most complaints and by far the most incidents connected to crashes—even before publicity sent the number soaring. This and other sources seem to indicate that Toyota has an exceptional problem. But when compared with the vast number of cars Toyota sells, the current reaction is wholly out of proportion.

Sudden acceleration in Toyotas over the last decade has been linked with—which doesn’t mean “caused”—52 deaths, according to NHTSA. It was just 19 before the current publicity. A Los Angeles Times investigation brought it up to 56, including those culled from lawsuits. Whatever the count and cause, that’s too many. But it’s also out of 20 million Toyotas sold, and out of the 420,000 Americans NHTSA says died in motor vehicle accidents that decade.

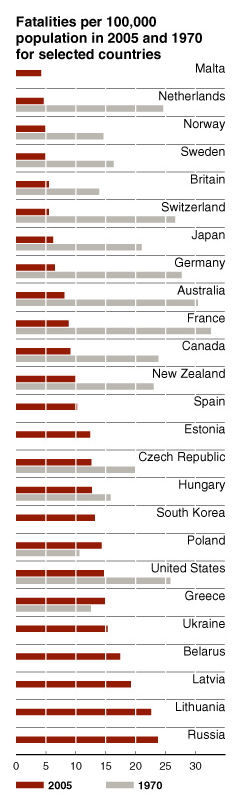

Defects kill very few drivers, generally drivers kill drivers. This graph shows Americans are particularly good at it.

Defects kill very few drivers, generally drivers kill drivers. This graph shows Americans are particularly good at it.

And although Toyota had almost 17% of total U.S. car sales in 2008, it accounted for merely 8% of total claims for deaths and injuries in the first quarter of that year, according to NHTSA. Edmunds.com found that while Toyota was third in U.S. car sales from 2001 through 2010, it was 17th in NHTSA complaints. Thus, even if every sudden-acceleration complaint proved valid, Toyotas are among the safest cars made.

Moreover, some of those reports surely could have been driver fault. To err is human; to blame errors on external factors is even more so.

Consider the Audi sudden-acceleration hysteria of two decades ago. In 1986, Kristi Bradosky, while driving an Audi 5000, ran over and killed her young son. “60 Minutes” aired a misleading segment depicting a runaway Audi—without disclosing that the car had been re-engineered to respond that way. Nor did it mention that Bradosky had told police that her foot had slipped off the brake onto the accelerator.

The rest of the media piled on, and a tsunami of Audi acceleration complaints linked to accidents swamped NHTSA—about 100 times more per vehicles sold [586/100,000] than those against Toyota. Yet investigations in Canada and Japan found no mechanical problems, and a NHTSA investigation declared the problem was “pedal misapplication,” though adding that the pedals must have been poorly placed.

While Audi was a niche carmaker, Toyota is the world’s second-largest producer, and for good reason. Despite getting bad press last year, it came out as far and away the top-quality automaker, according to Consumer Reports’ 2010 reader survey.

Toyota directly and indirectly employs about 200,000 Americans, and directly invests more than $18 billion in this country every year. The Toyota Camry, built in Kentucky and Indiana, is the most “American” car on the market, according to Cars.com.

Yet there’s another tragedy in this hysteria, some auto safety experts say: the wrong focus.

“Nobody wants to minimize any deaths Toyota defects may have caused,” says Russ Rader of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. “But vehicle defects are just a tiny, tiny part of what leads to crashes.”

Leonard Evans, author of the book “Traffic Safety,” also bemoans what he calls “the lethal American obsession with technical flaws.” Evans said: “Whether it’s ... defect or a child darting into the road, most crashes occur because drivers don’t leave an adequate safety margin.”

U.S. makers set the standard in safe vehicle design, according to the London-based FIA Foundation for the Automobile and Society. In 1970, the U.S. had the lowest fatality rate per miles driven. By 2005, it had fallen to 11th among industrialized countries. So why the emphasis on mechanical defects above all else? Evans says it began with Ralph Nader and his 1965 book, “Unsafe at Any Speed.” Today it’s perpetuated by trial lawyers seeking the deepest pockets and a media that know it’s sexier to crusade against corporations than emphasize individual responsibility.

“One hundred people are . . . killed every day, and it has nothing to do with technology, recent or otherwise,” says Evans. “We can cut that number by half by concentrating on driver attitudes.”

Defects can lead to terrible circumstances over which a driver has no control. I’ll never forget, nor will my wife, who now suffers from epilepsy that’s probably a result of the crash. But while it’s the extraordinary that makes for headlines and congressional demagoguery, focusing on the ordinary is what will truly save lives.