Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

The Gulf War Syndrome ‘Mystery’

March 01, 2010 · Michael Fumento · Independent Journalism Project · GulfGulf War Syndrome (GWS) is back in the news, thanks to a new study released by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), and so is the persistent effort to label it a “mystery.” See, for example, the story by a HealthDay reporter headlined “Gulf War Syndrome Is Real, but Causes Unclear: Report.” Says the article, “its causes, treatment, and potential cure remain unknown.”

A definite mystery, right? Well, no. There are two “causes” of GWS — the second of which is actually quite interesting, but not mysterious. The first explanation is a normal background rate of disease. That is, among the over 700,000 Americans who served in the Gulf War, there is no more sickness, and the death rate is no higher, than you’d expect in a group of that size and of those demographics after 19 years. This has been repeatedly demonstrated. A massive 2006 review of studies from four types of data sets — health-care registries, hospitalization studies, outpatient studies, and mortality studies — on American, British, Canadian, Saudi, and Australian veterans found that after 15 years there was “no suggestion that a new unique illness was associated with service during the Gulf War.” What part of “no” don’t the mystery-mongers understand?

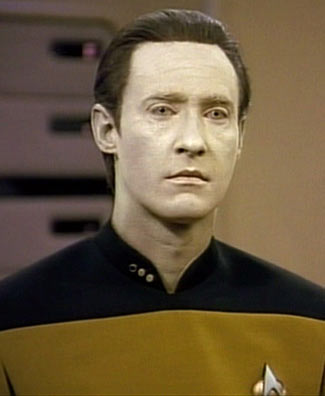

If you haven’t had a symptom of "Gulf War Syndrome," you’re probably an android.

If you haven’t had a symptom of "Gulf War Syndrome," you’re probably an android.

As I put it in an article for NRO in 2004:

Activists have attributed at least 123 symptoms to this “will-o’-the-wisp” syndrome, as former New England Journal of Medicine editor Marcia Angell described it to the New York Times. They include aching muscles, aching joints, abdominal pain, bruising, shaking, vomiting, fevers, irritability, fatigue, weight loss, weight gain, heartburn, bad breath, hair loss, graying hair, rashes, sore throat, itching, sore gums, constipation, sneezing, nasal congestion, leg cramps, hemorrhoids, hypertension, insomnia, and headaches.

Anybody who hasn’t had most of the above symptoms is probably an android. But when a non-vet gets a cough, it’s called “a cough.” If a Gulf vet gets one, it’s called GWS.

Still, there are different illnesses found among the Gulf vets, which brings us to the second cause. Like the 2006 review, the IOM report also found “no unique syndrome, illness, or symptom complex.” But it did find, on the basis of self-reports (rather than objective examinations), that Gulf vets had an unusually high incidence of “psychiatric disorders [such] as posttraumatic stress disorder, gastrointestinal disorders, joint pain, and respiratory disorders.” These are all classic symptoms of “mass psychogenic illness,” points out University of Toronto medical historian Edward Shorter, the author of From Paralysis to Fatigue: A History of Psychosomatic Illness in the Modern Era. But “psychogenic” or “psychosomatic” doesn’t mean “it’s all in your head,” as so many people believe. It simply means it originated in the mind. “There can be real subjective problems,” Shorter says. “It just means that they’re not organic — that they don’t have outside causes like depleted uranium or chemical exposure.” But the GWS “organic lobby,” as he puts it — meaning primarily veterans’ advocacy groups — “insists one or more of those have to be the cause.” Probably all of us have suffered psychosomatic illness. I once had a case of urticaria (hives) that would rate in the Guinness Book of World Records. My face would swell up like the Elephant Man’s. My limbs would resemble Popeye’s. It was sheer agony, and all the doctors were baffled. Then somebody suggested to me it was caused by a specific stress I had been suffering, and I realized he was right. Within days, the hives and the horror were gone forever. Mass psychogenic illness has been documented since the Middle Ages and today occurs frequently. Introduce a noxious odor into a high-school building, provide the least hint it may be harmful, and watch the kids start falling over like tenpins. “That’s how suggestion works,” says Shorter. “Tell people they’ll come down with X or Y, and then by golly they will.” And that’s just what our Gulf vets have been told, both by the press and by the lobby that thinks it’s helping them. That’s why Shorter calls GWS a “mediagenic” epidemic. In 17 years of covering this story, I’ve traced GWS from its initial outbreak among Indiana reservists, whence it went nationwide. Then after a pause it jumped to the U.K. and other English-speaking countries. Then finally, after another pause, it jumped to countries where the media are primarily non-English. Reporters, unfortunately, usually don’t understand what psychogenic means and think they’re doing vets a favor by offering outside agents as causes, no matter how unlikely they are. (Scud missile fuel, anyone?) And, yes, people have a taste for mysteries, and so the media want to perpetuate the GWS “mystery,” complete with riveting, though impossible, tales — as indeed they’re now doing with the Toyota “mystery.” (Cosmic rays, anyone?)

Sure, GWS is a mystery. So are these.

Sure, GWS is a mystery. So are these.

With marauding Toyotas, no tale is too outlandish to be believed. The California “runaway Prius” driver tells credulous reporters he was “afraid” to try to shift into neutral because he needed both hands on the steering wheel; yet they know he had a cell phone in his hand almost the entire time. Subsequently, newspapers worldwide carried a story about a Norwegian driver who claimed he had to smash his runaway Prius into a guard rail at over 100 mph to stop it; yet accompanying photos showed mere scratch marks on the fender. GWS gave us “Brian Martin and the Amazing Technicolor Vomit.” Pfc. Martin, who belonged to my old airborne brigade, told Congress in 1996 — and told me twice, and therefore almost certainly every other reporter who interviewed him — that after returning from the Gulf, “every morning” for ten straight months “I would vomit Chemlite-looking fluids” during the daily run in physical training, and “an ambulance would pick me up, putting IVs in both arms.” Chemlites are sticks that glow in the dark when you snap them. Do we really believe that his superiors would force him through such an ordeal more than once, let alone every day for ten straight months? The media acted as if they believed it. As far as I’ve seen, nobody but me ever questioned this or Martin’s other amazing stories. Indeed, when I called an AP reporter and asked if she didn’t think the glowing-vomit remark impugned Martin’s credibility, she said no. “You have to remember he’s been on talk shows, and they’ve written a lot about him.” John Hanchette, then with Gannett News Service and a 1980 Pulitzer Prize winner, also wrote about Martin’s testimony. And while (like the AP reporter) carefully excising mention of the glowing vomit, Hanchette did list a number of bizarre symptoms Martin had claimed, saying they had been confirmed by “federal medical exams.” That gave them a real air of authority. Yet Martin’s doctors told me that some of the symptoms hadn’t been complained of by any other of their Gulf vet patients. Hanchette did not return repeated phone calls seeking comment. His editor, Jeffrey Stinson, told me, “I’m not going to sit here and go over this kind of stuff with you. You can sit here and nitpick. He’s a Pulitzer Prize winner.” Stinson then hung up. Obviously winning a Pulitzer means never having to say you’re sorry. Perhaps you can argue that if we demand mysteries, the media are merely doing us a service in providing them. But there can be a dark side. Is this how we should repay 700,000 people who sacrificed of themselves for us? Says Shorter, “I don’t think you’re doing these men any favor by encouraging them to think they have a terrible organic disease they don’t have.”