Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Michael Fumento: Holes and All, Bioshield Needed

January 01, 2004 · Michael Fumento · Scripps Howard News Service · MilitaryFeel safer knowing that eagle-eyed airport screeners are snatching sewing scissors from your carry-on luggage? No, because you probably realize that an airliner-as-missile redux would surely fail since passengers and crew would pummel the perpetrators. The "ideal" next terror attack will not only be horrific but hard to stop – which puts biological weapons on the short list.

Horrific, but it’s been done. The next attack will come in a completely different way.

Horrific, but it’s been done. The next attack will come in a completely different way.

That’s why President Bush in his 2003 State of the Union Address announced Project Bioshield, proposing that $5.6 billion be spent over the next 10 years to defend against germ attacks. The House of Representatives quickly passed it 421-2, the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee (HELP) Committee approved it unanimously, and then the full Senate promptly ... sat on it. Since then, "Senate" has become "senator" – specifically Michigan Democrat Carl Levin, who believes politics should take precedence over national security.

BioShield is intended to streamline government research and provide private industry money to develop products which the government will then procure. In the event of a national emergency, it also gives the president authority and flexibility to authorize use of medical products not yet FDA-approved.

That’s the sticking point. Levin "is concerned that the bill will allow the White House to dole out large, no-bid contracts," the Global Security Newswire reported in January.

Levin prides himself on being "an effective waste fighter."

But "It’s going to be awfully hard to explain to perhaps millions of Americans (exposed in an attack) that we can’t provide an available remedy because we might not have given all companies an equal chance to make bids," says Gayle Osterberg, spokesperson for the Senate HELP Committee. Levin’s office did not return my calls.

Meanwhile, the "delay has had a sobering effect within the industry, causing doubt that any investments made to develop new countermeasures against potential bioterror agents will ever pay off," Claire Fraser, president and CEO of the Institute for Genomic Research wrote recently in Science magazine.

Look no further than the ABthrax vaccine under development by Human Genome Sciences in Rockville, Md. The current anthrax vaccine comprises six injections received over an 18 month period – hardly ideal for an emergency. But in early human testing, ABthrax seemed to provide quick and safe protection with a single injection.

Fortunately, as the Japanese found out, fleas are not good at taking orders.

Fortunately, as the Japanese found out, fleas are not good at taking orders.

"However," states the HGS Web site, "further development of ABthrax is dependent on the government’s willingness to commit to its purchase, either under existing authority or under Project BioShield." There is no private market for anthrax vaccinations and small biotech companies have no resources to donate to Uncle Sam. It’s not that BioShield doesn’t have its problems.

For one, it’s grossly underfunded. Six billion bucks can fund plenty of good research but can’t hope to provide for procuring necessary finished products. "We would completely break the bank if we committed to purchasing every one," says Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The legislation also overemphasizes those germs celebrated by Hollywood and the media but that would make poor weapons, such as Ebola virus and plague. Ebola is terribly hard to catch, requiring exposure to bodily fluids such as in health care or mortuary settings.

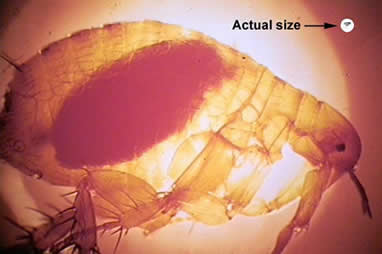

And while the word "plague" strikes fear into the human heart, it can’t do much harm without the right combination of fleas and rats to spread it. That’s what Japan’s notorious Unit 731 discovered in World War II when it tried repeatedly to bomb Chinese civilians with infected fleas. BioShield also relies too heavily on vaccines.

"We need to emphasize drugs that can be administered quickly after exposure," Dr. Ken Alibek, executive director of George Mason University’s Center for Biodefense at Manassas, Va., told me. Alibek, who headed the Soviet bioweapons program until his defection in1992, said, "That’s more sensible than trying to protect the entire population before an attack that may never come."

Vaccines also provide fairly narrow protection because they promote the development of specific antibodies. But antibiotics and some antiviral medicines have already shown the ability to fight a broad spectrum of diseases including the worst of all - those not yet even invented.

But all this can be dealt with later. We need BioShield now. We know exactly when foreign terrorists will attack with bioweapons: As soon as they can.