Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Covering Iraq: The Modern Way of War Correspondence

January 01, 2006 · Michael Fumento · National Review · MilitaryRamadi, Iraq

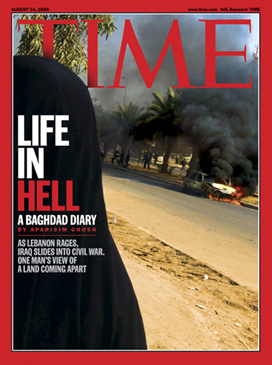

Would you trust a Hurricane Katrina report datelined ”direct from Detroit”? Or coverage of the World Trade Center attack from Chicago? Why then should we believe a Time Magazine investigation of the Haditha killings that was reported not from Haditha but from Baghdad? Or a Los Angeles Times article on a purported Fallujah-like attack on Ramadi reported by four journalists in Baghdad and one in Washington? Yet we do, essentially because we have no choice. A war in a country the size of California is essentially covered from a single city. Plug the name of Iraqi cities other than Baghdad into Google News and you’ll find that time and again the reporters are in Iraq’s capital, nowhere near the scene. Capt. David Gramling, public affairs officer for the unit I’m currently embedded with, puts it nicely: ”I think it would be pretty hard to report on Baghdad from out here.” Welcome to the not-so-brave new world of Iraq war correspondence.

Vietnam was the first war to give us reporting in virtually real time. Iraq is the first to give us virtual reporting. That doesn’t necessarily make it biased against the war; it does make it biased against the truth.

C-130 Hercules shooting off flares to divert heat-seeking missiles. They’re wonderful machines, but don’t do "corkscrews."

Moreover, you can read similar corkscrew horror stories from reporters who have flown in on C-130s. ”A C-130 deposits us onto the tarmac of Baghdad International Airport after a hair-raising corkscrew landing intended to elude incoming small arms and rocket fire,” a Greek freelance photojournalist boasted on his blog.

It’s not just experience that tells me that’s baloney. Look at a photo of a C-130; it’s a flying bathtub.

Chuck Yeager couldn’t throw it into a corkscrew and then pull out. I did ask a crewman on this last trip about deep-diving C-130s and he said that on a single flight (out of hundreds) the pilot had to plunge suddenly to avoid getting to close to another plane, but other than that ”Landing in this plane is like landing in an airliner.” Except that unlike those Fokkers there are no flight attendants.

As to the overall dangers of flying into or out of Baghdad, one civilian cargo jet was hit after takeoff with a shoulder-launched missile, but landed safely; and one Australian C-130 was hit by small-arms fire, killing one passenger. That’s it. No reporter has been injured or killed flying into or out of Baghdad International.

The Highway of Death

Then there’s the dreaded ”Highway of Death.” Here’s Ghosh again, picking up after his horrific corkscrew description. ”But the relief is temporary; most of us still have to negotiate the Highway of Death,” he writes. ”There have been hundreds of insurgent and terrorist attacks along its length since the U.S. military established its largest Iraqi base,

Camp Victory, next to the airport three years ago. Many of the attacks are directed at U.S. patrols, but they have also killed scores of Iraqi noncombatants.” Only as an afterthought does he note that ”recently the highway has become less deadly.”

And here’s an account from A. A. Gill, a reporter who accompanied another journalist, Jeremy Clarkson, in Iraq last year. He wrote, in Britain’s Sunday Times Magazine last November:

The Americans didn’t have a Black Hawk to spare for the five-minute hop into the Green Zone, so we were going to have to drive it. This is the bit Jeremy swore he’d never do. When you’re asked where you draw the line, this is the place to start drawing. Nobody drives into Baghdad if they’ve not been given a direct order. Even our minder, Wing Commander Willox, has never done it. . . . This road is code-named Route Irish. [The] Guinness [Book of] World Records has just authoritatively announced that Baghdad is the worst place in the world. . . . This 25-minute stretch of blasted tarmac from the airport to the Green Zone is, as Jeremy might say, the most dangerous drive—in the world.

Yet just two days earlier the Washington Post headlined a piece on Route Irish as follows: ”Easy Sailing along Once-Perilous Road to Baghdad Airport.” It observed, ”Two months ago, the killings stopped. In October, one person was wounded on the road and no one was killed, according to the U.S. Army. . . . It was safe enough to stop here, to linger, to chat, and a computer screen flashed the statistical evidence. . . . In 10 months, the only enemy fire they have seen on the airport road came after one of the civilian trucks they were escorting broke down.” And two months earlier, USA Today had published a similar account, backing it up with a quote from an officer whose men patrolled the roads: ”Route Irish is definitely not the most dangerous road in Iraq any longer, and everyone who uses it knows it.” Apparently, though, the Sunday Times reporter didn’t know it—and other Baghdad journalists still don’t know it.

In fact, only reporters call it ”The Highway of Death.” To everyone else it’s Route Irish, named after the Fighting Irish of Notre Dame (and not after an infantry regiment with strong Irish roots, as is widely believed).

The indestructible Rhino

Further, reporters coming into the city or the IZ often have the option of bypassing Route Irish in the aforementioned helicopter runs. Failing that, they can take the Rhino bus. The Rhino is so thickly armored that by comparison an M1 Abrams tank is made of cardboard. It’s repeatedly been hit with IEDs, causing no more discomfort to passengers than ringing ears. Basically the IED would have to be atomic to stop it. But in that case, the passengers would still be protected by soldiers on board firing through gun slits, by heavily-armed Humvees both fore and aft, and by a helicopter gunship that flies over it.

Yet reporters such as NBC News State Department Producer Libby Leist, make even the Rhino ride sound scary — though at least she didn’t claim the bus makes a corkscrew plunge.

Telling readers that the Blackhawk intended to fly Condoleeza Rice and her entourage of aides and reporters couldn’t fly to the IZ on account of weather, Leist wrote in March 2006 (five months after the aforementioned Washington Post account, and seven months after the USA Today account), ”Now, even the hardened journalists and Rice’s well traveled aides seemed leery. We had to take ’Rhino’ military vehicles out onto Baghdad’s famously dangerous airport road. The only thing we could take comfort in was that Rice’s security detail thought it was safe enough for her to do.” Leist concluded that, ”Needless to say, it was a relief to finally get into the heavily guarded secure International Zone . . . . The usually energetic press corps was silent for the entire ride from the airport — a sign we were all anxious to get off the road.” Chin up, Libby! Now you’ll have something to tell your grandchildren about.

Fear and Tension in the IZ

Much of the public’s image of the Iraq war is generated from this hotel, Baghdad’s Al Rashid.

With that horrific arrival behind them, it’s time for the Baghdad reporters to settle into their lodgings. Those may be in the International Zone or just outside in places like the Al Rashid, Al Hamra, or Palestine hotels. And trust them, their trip into the IZ was stepping from the frying pan into the fire. Newsweek’s Joe Cochrane wrote a commentary about the IZ in July 2005 just two months after I first visited it. (All media must come through the IZ to get credentialed.) In other words, we both saw the same place at about the same time—but I don’t recognize his IZ.

”I’ve always been something of an optimist, but everyone has a breaking point. Mine came on Saturday as I toured the infamous ’Green Zone’ in central Baghdad,” Cochrane began. After providing his view of a mean Baghdad outside the IZ, he continued, ”The situation inside the [IZ] is scarcely better. Heavily armed troops guard government buildings and hospitals, menacingly pointing their weapons at anyone who approaches. Soldiers manning checkpoints can use deadly force against motorists who fail to heed their instructions, so the warning signs say, and I have no doubt they’d exercise that right in a heartbeat if they felt threatened. All this fear and tension, and inside a six square mile area that’s supposed to be safe.”

That’s funny, because inside my ”infamous” IZ the guards make people feel safe, not threatened. In 2005, many of them were Gurkhas—a combination of some of the best killers on earth and the politest people you’d ever want to meet. Nobody ever menacingly pointed a weapon at me.

Heavy damage from an attack on the IZ — from American aircraft in 2003.

Cochrane was right that ”roadblocks, blast walls, and barbed wire are the most common sights in this walled-in mini-city,” but these defenses contributed to an atmosphere that to me was devoid of fear and tension. As for the idea that it’s ”supposed to be safe,” when I inquired in May 2005 I was told it had probably been months since anybody dropped in a rocket or mortar round. And ”dropped in” is probably the best term; the bad guys don’t even have the capacity to aim; they just fire and run, hoping the round actually lands somewhere within the zone. It’s rare that they actually hit near, much less kill, anybody.

The real IZ represents opulence in the midst of war—with terrific chow, huge post exchanges that stock an amazing array of products, the best medical care in the country, and large, sumptuous swimming pools built for Saddam but now open to anybody who works in the zone. Nor have the grotesque exaggerations of the dangers of the IZ gone unnoticed by soldiers and their loved ones. ”Dear Chain-smoking, Unwitting Stooges,” military blogger Jason Van Steenwyk began an open letter to the Baghdad press corps. ”So how come we can get mortared several times a week out here and it never makes the news, but the pogues [rear-echelon soldiers] in the Green Zone can catch three measly mortar rounds and I get my dad emailing me asking why the Baghdad press corps is covering it like it’s the second Tet Offensive?”

(Not incidentally, soldiers in the IZ also feel the need for false bravado. This past spring, on a tour of the area while waiting for my helicopter to come that night, I was accompanied by a chubby sergeant armed to the teeth including five hand grenades on his vest while soldiers I’ve gone into combat with never wear more than one. Obviously insecure about living in Iraq’s lap of luxury while other soldiers throughout the country lived in more primitive conditions and actually fought and died, he explained that the IZ can be an extremely dangerous place and that if often gets shelled. Fortunately he didn’t hear the sound of my eyes rolling.)

In any case, no reporter has been killed or injured inside the IZ.

Hotel Hell

My shared accommodations at camp Corregidor. No sink or shower, not enough room to go through your equipment without hauling it outside, and almost no protection from incoming mortars or rockets.

Then you have those awful, oh just awful, hotels! CNN’s Jane Arraf dared me to visit one. I was stunned; it was as if somebody had dared me to zip my pants. Really, I thought, just how often do you get mortared while inside one of those hotels? She did point out that reporters have been killed inside Baghdad hotels. But they were not Americans and were not killed by enemy fire, but rather errant American fire during the seizure of Baghdad way back in early 2003.

I recall another reporter complaining that the hotels were so bad that you felt compelled to go out and buy your own linen. Apparently far better to bundle into or atop a sleeping bag in a cracker box at the forward operating bases I’d stayed at in Fallujah, Karma, and here in Ramadi or the 80-bed transient tent at Camp Ramadi with nothing over your head to protect you from rocket or mortar rounds but a sheet of canvas or perhaps a layer of sandbags on wood that can stop a 60 millimeter mortar but not an 81 or 120 millimeter, which the enemy greatly prefers.

Where I am right now it’s mandatory to wear body armor and helmet at all times unless in a fortified position. It’s hot and it’s a hassle. Imagine getting up in the middle of the night to relieve yourself and having to slap on clothes and armor to walk to a nasty outhouse. You may have to urinate in one place and do your other business in another, because urine interferes with the burning of the excrement.

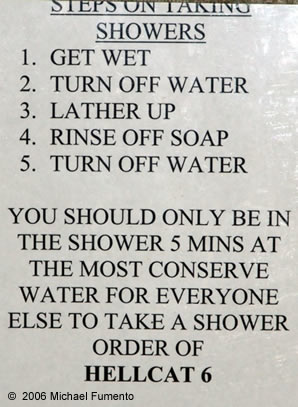

A sign at Camp Corregidor

To take your shower you get wet, turn off the water and lather up, then quickly rinse off. And no, there’s no place to plug in your hair dryer. On the other hand, in some camps I’ve stayed at there aren’t any showers so you don’t have to worry about any of this.

You’ve probably heard the Iraqi desert is made of sand; you know, like Malibu Beach. Wrong. It’s a fine dust that coats everything including the inside of your lungs. Until recently there was no store of any kind at Corregidor. A truck came once monthly and if you needed something in-between — tough.

Even getting onto one of the nine Internet-connected computers that are somehow slower than dial-up and allocated for 500 men makes sending off dispatches — or sending an email to your spouse to tell her you’re still okay despite the fighting in your area he or she heard about — rather difficult.

Hiding out in Baghdad

It’s not fair to say the hotel-dwellers never leave their safe and comfy confines. ”Despite the danger, Nancy [Youssef, Knight Ridder bureau chief] and her colleagues do venture out and do find inventive ways to talk with ordinary Iraqis,” then—Knight Ridder D.C. bureau chief Clark Hoyt wrote in a column. He explained that Nancy says, ”When I go grocery shopping, I listen to people’s conversations. What are they talking about?” So this is what passes for ”war correspondence” of the Baghdad Brigade.

Even journalists sympathetic to the Baghdad press corps admit they essentially just hide out. Here’s how The New York Review of Books put it last April: ”The bitter truth is that doing any kind of work outside these American fortified zones has become so dangerous for foreigners as to be virtually suicidal. More and more journalists find themselves hunkered down inside whatever bubbles of refuge they have managed to create in order to insulate themselves from the lawlessness outside.” Unless you accept ”insulation” as a synonym for ”reporting,” this doesn’t speak well of the hotel denizens.

Other reporters have been less generous. The London Independent’s Robert Fisk has written of ”hotel journalism,” while former Washington Post Bureau Chief Rajiv Chandrasekaran has called it ”journalism by remote control.” More damningly, Maggie O’Kane of the British newspaper The Guardian said: ”We no longer know what is going on, but we are pretending we do.” Ultimately, they can’t even cover Baghdad yet they pretend they can cover Ramadi.

Michael Kelly

Embeds die in Iraq, not members of the Baghdad Brigade.

One way the Baghdad press corps and its allies try to steal valor is to invoke the incredibly large number of reporters killed in the war: It’s true that over 100 journalists or media assistants have been killed. Yet, with the sole exception of Steven Vincent, the only American journalists killed or even seriously injured by hostile action in Iraq have been embeds. Atlantic Monthly editor-at-large Michael Kelly (an editor of mine) drowned after his Humvee rolled into a Baghdad canal during the invasion. NBC reporter David Bloom died of a pulmonary embolism from being cramped in a Humvee, also during the invasion. Both were embedded with the 3rd Infantry Division.

CBS News cameraman Paul Douglas and freelance soundman James Brolan were blown up by an improvised explosive device (IED) while accompanying CBS correspondent Kimberly Dozier, herself critically injured. They were embedded with the 4th Infantry Division. So were ABC anchorman Bob Woodruff and his cameraman, who were critically injured by an IED. Time correspondent Michael Weisskopf had his hand blown off trying to toss a grenade out of his Humvee when he was embedded with the 1st Armored Division. These, not the hotel-bound credit-claimers, are the journalist-heroes of the Iraq War.

To Tell the Truth

Of course, there are exceptions to MSM cowardice and the false bravado that follows. The Associated Press often sends reporters into Ramadi. USA Today does likewise, actually embedding a woman blogger in the city. The Washington Post sends many fine reporters where other news bureaus fear to tread. There are surely other exceptions.

Yet the glaring gap between the reality of the Iraq war and the virtuality from the hotels and IZ is what leads embeds to go to the most dangerous places in Iraq and Afghanistan on their own dime.

One of them made this point quite forcefully in a recent column. Jerry Newberry, communications director for the Veterans of Foreign Wars and a Vietnam Army vet, wrote in a September column just before heading off for Afghanistan and then Iraq: ”For the most part, the wars being fought by our people in Afghanistan and Iraq—their successes, heroism, and valor—[are] reported by some overpaid, makeup-wearing talking heads, sitting on their fat rear-ends in an air-conditioned hotel. They rely on Iraqi stringers to bring the stuff to them and then call it reporting.”

Newberry’s bravery and dedication are to be saluted, but as a combat vet he has advantages. So did I, as a veteran paratrooper (on my first trip) and a combat veteran (by the end of my second). Michael Yon, famed for his blog and award-winning photos of his nine-month embed with the infantry in Iraq is a former Green Beret. Writer and historian Andrew Lubin, a Fallujah-bound embed I met while getting credentialed on this trip, is a former Marine who goes to the rifle range twice monthly.

But Patrick Dollard, with no military training, left a cushy job as Oscar-winning director Steven Soderbergh’s agent to bunk down with Marines in Ramadi for seven months to film a documentary series (still being edited) that he hopes will show the real war and the real warriors.

Patrick Dollard, from La La land to insurgent hell

In February, a Humvee he was traveling in hit a massive IED, which shredded the vehicle and killed two of the three Marines aboard. Dollard was injured and hospitalized. But he had a mission, and was quickly back on the job. The next month, another IED blast injured him, less seriously. Then . . . right back to work. Dollard’s experiences alone put the Baghdad press corps to shame. But he insisted to me that exchanging Hollywood for a hellhole wasn’t as hard as you’d imagine. ”I had to feel the moral imperative to go, and clearly I did feel it,” he said.

The sad truth is that the mainstream media have no interest in covering the Iraq War for what it is, observes Dollard. He says they are interested in Iraq only so far as it is useful as a weapon against their self-imagined mortal political enemy, George W. Bush. The embeds, however, want the real picture—and we want to tell the truth about it to the world.

Which is something their detractors simply refuse to understand. Screenwriter-director Nora Ephron says that dispatches from both soldiers and embeds are worthless, because we’re ”too close” to the war. The best ”reporting” apparently is from those most removed. (Amazingly, Ephron also believes embedding was an evil idea dreamed up for this war, even though in World War II and later wars all major news outlets had reporters with the troops on the front lines. That’s how we got the incredible dispatches of Ernie Pyle, and the wonderful Iwo Jima flag-raising photo by Joe Rosenthal.)

Sometimes you’ll hear that embeds are just shuffled around in armored vehicles. Some are, although IEDs and rocket-propelled grenades still make that less safe than manning a desk. But in my case, I’ve never been in an armored vehicle that wasn’t merely dropping us off at a remote location to engage in foot patrols. Yet Paul Rieckhoff, an anti-war vet who was hawking his boring book, Chasing Ghosts, on the same Al Franken Show Jane Arraf and I were on, commented on my disgust with hotel-bound reporters by smearing embeds. He labeled those who actually go into battle with troops as ”jock sniffers.” To him, the Ernie Pyles and Joe Rosenthals of America’s past were just a bunch of contemptible groupies.

The most iconic image of World War II, by ”crotch-sniffer” Joe Rosenthal.

Yet embeds perform a service beyond just their willingness to see combat, and to describe accurately the specific events they witness. ”Although some journalism professors may worry that military embedding is subverting the media, I would argue the contrary,” Robert Kaplan wrote in The Atlantic Monthly. Kaplan, who has been embedded all over the world, went on to observe, ”The Columbia Journalism Review recently ran an article about the worrisome gap between a wealthy media establishment and ordinary working Americans. One solution is embedding, which offers the media perhaps their last, best chance to reconnect with much of the society they claim to be a part of.”

The media-elite Baghdad Brigade and its stateside editors have forfeited this opportunity. It’s not just that being with the soldiers puts them at risk, but that they don’t want to be with those soldiers. They prefer the company of their fellow journalists and that, too, contributes to their unwillingness to leave their walled-in compounds.

It’s impossible to blame anyone for not wanting to report from the more dangerous parts of Iraq; over 99 percent of Americans surely would not want to. The trouble with the Baghdad press corps is that, in pretending to be war correspondents when the correspondence they engage in could just as well be done from New York or Washington, they may well be squeezing out from those positions reporters who actually want to do the job. Harry Truman’s famous words, ”If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen,” suggest wise advice to today’s journos in Baghdad: If you don’t have the guts actually to cover the war, stand aside for those who do.