Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Cobbling Together a Crisis: From a Swine Flu Epidemic that’s Peaked

September 02, 2009 · Michael Fumento · The Independent Journalism Project · Swine flu“Swine flu has killed 540 kids, sickened 22 million Americans,” screamed USA Today’s page 1 headline, sub-headed “CDC: Cases, Deaths are Unprecedented.” “Swine flu cases in the U.S. are rising at the fastest pace for influenza in four decades,” breathlessly declares a Bloomberg News article lede. Another article’s title referred to a “national swine flu spike.”

Scary stuff! Phony stuff! And a desperate effort to distract from an alarmist media’s greatest nightmare: That the epidemic has peaked.

The latest squealing is based on the new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that 22 million Americans have been infected with H1N1 swine flu from when the outbreak’s early April beginning until October 17, or five and a half months. (Though “sickened” hardly applies since about a third of cases are wholly asymptomatic.) Of those, the agency says 4000 have died and 540 were under age 18.

The latest squealing is based on the new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that 22 million Americans have been infected with H1N1 swine flu from when the outbreak’s early April beginning until October 17, or five and a half months. (Though “sickened” hardly applies since about a third of cases are wholly asymptomatic.) Of those, the agency says 4000 have died and 540 were under age 18.

Put in perspective with garden variety seasonal flu these figures aren’t at all alarming and the CDC’s report indeed provides seasonal flu data. But perspective – like honesty – is the alarmists’ enemy. So instead reporters simply cut, rearranged, and pasted press conference statements from unofficial swine flu “czarina” Dr. Anne Schuchat, director of the CDC’s Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

Thus Schuchat’s reference to “unprecedented” had nothing to do with absolute numbers of infections or deaths, but merely the time of year at which they were occurring. That’s because swine flu spreads more easily at warmer temperatures. Normally flu doesn’t get into stride until early January and then peaks in mid-February.

The figures themselves are far from “unprecedented.” The CDC estimates 5 to 20 percent of the population (15 to 60 million people) gets the flu in a typical year, with almost all cases occurring from January through April. That’s as many as 15 million a month compared to 22 million spread over five and a half months.

What’s truly unprecedented about swine flu is its incredible mildness. The CDC estimates seasonal flu annually kills 36,000 Americans, again spread over four months. That compares to 4,000 swine flu deaths over five and a half months. The seasonal flu death rate therefore ranges 0.06 percent to 0.24 percent, while the CDC estimate puts it at only 0.0182 percent for swine flu. So seasonal flu is three to 12 times deadlier per case.

Likewise for the world scene. When the World Health Organization (WHO) made its official pandemic declaration in June, we were 11 weeks into the outbreak and swine flu had only killed 144 people worldwide – the same number who die of seasonal flu worldwide every few hours. After seven months, swine flu has killed about as many people as the seasonal flu does every seven days.

The media also used Schuchat to invoke the horrific Spanish flu 1918-19, in which about 675,000 Americans died out of a much smaller U.S. population. CNN.com paraphrased Schuchat saying, “The prevalence of flu cases is higher than at any time since the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic.” Utterly false. Her only reference to the calamity was “what we’re seeing with this H1N1 virus is nowhere near the severity of the 1918 pandemic.” Apparently something got lost in the translation.

As for children, they do represent a disproportionately large percentage of those afflicted with and killed by swine flu compared to the seasonal variety, but it’s merely a larger slice of a vastly smaller pie. There are no good data on children’s seasonal flu deaths, but if they represented merely 3 percent of the total that would be 1,080. Mind you, that’s per season. The 540 swine flu figure is actually spread over two seasons.

As for children, they do represent a disproportionately large percentage of those afflicted with and killed by swine flu compared to the seasonal variety, but it’s merely a larger slice of a vastly smaller pie. There are no good data on children’s seasonal flu deaths, but if they represented merely 3 percent of the total that would be 1,080. Mind you, that’s per season. The 540 swine flu figure is actually spread over two seasons.

Now time for a bit of that irritating perspective again. Every year, 50,000 Americans perish before age 18, with 5,000 below age 15 dying of preventable accidental causes alone according to the National Safety Council. Eleven hundred are just from drowning.

Not that the CDC has totally clean hands. When Schuchat said “I am expecting all of these numbers, unfortunately, to continue to rise,” she meant in cumulative terms since the report was all about cumulative numbers. Like, duh, we thought swine flu had suddenly vanished.

Piqued over the Peak

But Schuchat knew or should have known it would be interpreted to mean on a per-week basis. For just as swine flu arrived early, so too must it peak earlier. Indeed, it already has as data readily available on the CDC FluView website and elsewhere – and just as readily ignored – show.

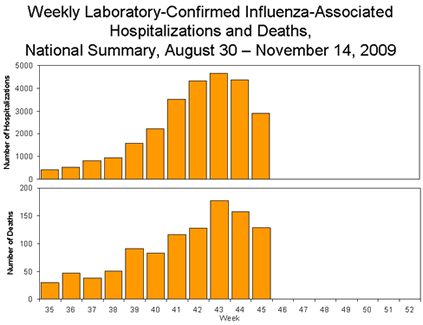

The first accompanying graphic from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows both new deaths and hospitalizations down sharply for the second week in a row, with hospitalizations at the lowest level since early October.

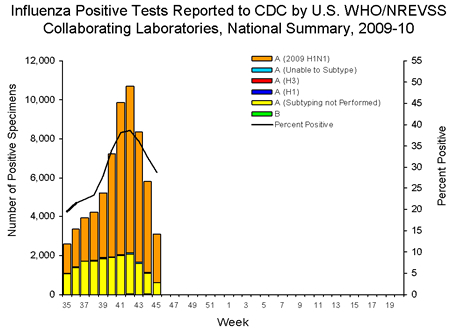

Even more telling, though, is that the bottom has fallen out of new infections as shown by the second graph. Test samples doctors have submitted to CDC-monitored surveillance laboratories show that four weeks ago almost 25,000 were sent and of those over 38 percent were positive. It’s steadily fallen each week so that the latest figures now show fewer than 29 percent positive out of merely 11,000 samples (the fewest samples since September), almost a 70 percent plunge from the height of the epidemic!

(And yes, don’t you think you should have read about this in the New York Times or Washington Post first?)

The American College Health Association’s latest weekly survey of CDC-defined “influenza-like illness shows college campus cases plummeted last week by 27 percent. Another bad spot of bad luck for those claiming swine flu threatens to wipe out the younger generation.

The number of states the CDC reports with “widespread” flu activity has also declined, from 48 at the height to 43 this week.

But could these indicators start to shoot up again? Not likely.

According to Farr’s law, named after 19th century epidemiologist John Farr, infectious disease patterns follow a bell curve. As the disease first plucks low-hanging fruit infections rise rapidly, but as fruit gets harder to reach the rate of increase slows until finally infections start falling off either to zero or to a lower “endemic” level.

To see swine flu isn’t somehow a Farr’s law scofflaw, look to Australia. Since it’s in the southern hemisphere, the Aussie flu season has ended. Almost all cases were swine flu and there was no vaccine. Its epidemic curve indicates that, yes, once swine flu cases started going down they kept dropping.

But no, the bell wasn’t symmetrical and don’t expect it to be here. Expect a long “tail” extending to the end of normal flu season in April. In other words, just because infections have peaked doesn’t mean we’ve necessarily seen half yet.

But that should actually prove to be good news. Consider that even without a vaccine, Australia along with New Zealand reported significantly fewer flu deaths than in normal years. Why?

The newly-released CDC estimate of infections and deaths U.S. indicates seasonal flu is anywhere from three to 12 times deadlier than is swine flu. Other data, such as from New York City data, also indicate swine flu is far milder. Yet swine flu spreads more easily, essentially outcompeting seasonal flu. In doing so, it’s essentially acting as a vaccine against its far deadlier cousin in the same way that the father of vaccinations, Edward Jenner, observed that cowpox protected dairy workers from the often-deadly and horribly disfiguring smallpox.

Swine flu, therefore, causes minus flu deaths.

Happily, even the U.S. "hysteria curve," as indicated by emergency room visits for people worried they have the flu – and worried enough to seek medical attention – is finally coming down from the highest level of any flu season in the 21st century. You can probably credit part of that historical hysteria to Obama’s October 23rd "national emergency" declaration. Nothing like an official pronunciation to send people with slight fevers – real or imagined – into fever pitch.

Then again, perhaps the Administration can argue that extra work hours put in by exhausted health care personnel, along with all those story opportunities for a sensationalist media, are stimulating the economy.

But more probably the Administration’s posturing, including ignoring the rapidly falling numbers, reflects H.L. Mencken’s observation that government ever seeks "to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary."