Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Breast Cancer and Herceptin Hype

October 21, 2005 · Michael Fumento · Scripps Howard News Service · Disease

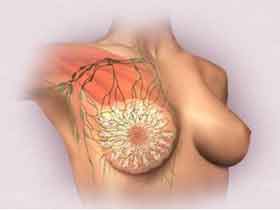

Breast cancer sometimes spreads to areas beyond the initial tumor via lymphatic vessels. In these cases, among the subset of women who overexpress the HER2 protein, Herceptin can help.

If I wrote about every hyped medicine, I’d have to do three columns a day. So at first I was going to give a pass to the irrational exuberance over the breast cancer drug Herceptin. But the nonsense just kept piling on and it’s all so horribly cruel to the 215,000 women who will contract breast cancer this year.

In case you somehow haven’t heard, three new studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine show that this cancer, which last year killed over 40,000 women, is now cured. Yes, that’s the exact word.

Among the headlines worldwide:

- "Drug Touted As Cure for Breast Cancer" (Associated Press)

- "Breast Cancer Is ’Cured’ By Wonder Drug, Say Doctors" (Sunday Times, London)

- "Breast Cancer Curable" (Daily Times, Pakistan)

- "Miracle Cure for Breast Cancer at Half the Price" (Daily News & Analysis, India)

And it’s all a lie, false hopes for every woman who has or will get breast cancer until there really is a cure.

To know anything about Herceptin is to know this is mammarial mendacity. Long before this $48,000-per-year drug was first approved in 1998 for cancers that have spread beyond the breast, it was known to be worthless in all but about 20-25% of women whose tumors pump out too much of a growth hormone receptor called HER2.

Further, responsible doctors don’t even use the word "cure" except with patients. Instead, the term they use is "survival," with five years arbitrarily chosen as the cut-off. (A friend of mine "survived" cancer, having had it seven years; we buried her last year.) The longest any of the women in the latest studies were followed was four years and for many it was only one year, far short of the standard measuring stick.

Herceptin is clearly helpful for a small minority of women with breast cancer, but it’s no panacea.

But okay, these "minor" matters aside, just what did those new studies say?

One looked at the incidence of breast cancer recurrence in women who had already undergone surgery, followed by either chemotherapy or radiation treatment. They were split into three groups of which one received Herceptin for a year, one for two years, and one got no Herceptin.

The trial is ongoing, but at one year there were 127 breast cancer recurrences in those treated with Herceptin and 220 in those who received a placebo. That seems impressive, but I’ll bet those 127 women don’t feel very cured. Further, Herceptin recipients were no likelier to be alive than non-recipients.

The second paper, comprising two studies, looked at Herceptin as a companion to a drug called paclitaxel and chemotherapy. Three-year survival was 94.3% for those who receiving Herceptin, 91.7% for those who were not. Of Herceptin recipients, 90% had no distant spread of their cancer compared to 84% of women on paclitaxel and chemo alone. Those are significant differences. But again, 6% of the "cured" women were dead within just three years.

So where did this "cure" talk come from? Don’t blame Herceptin maker Genentech, which issued an appropriately milquetoast press release. This disinformation was your tax dollars at work.

It originated with Dr. Jo Anne Zujewski head of breast-cancer therapeutics at the government’s National Cancer Institute. "In 1991, I didn’t know that we would cure breast cancer," she exclaimed of the studies, "and in 2005, I’m convinced we have." The Associated Press shot that line ’round the world and ("investigative reporter" having become essentially oxymoronic) it was repeated endlessly. Why read a study when you can just quote somebody?

"This thing is out there now and there’s no pulling it back," an angry Barbara Brenner, Executive Director of Breast Cancer Action in San Francisco, told me.

Brenner’s got good reason to be mad. She knows that hopes raised so high will soon be dashed. Further, "Now the public is going to think the breast cancer problem is solved." Five-year breast cancer survival has increased significantly in recent decades but always from incremental progress, never from miracle breakthroughs. And the problem is hardly solved.

"Really, we’re trying to unring a bell," say Brenner. "And how do you do that?"

I don’t know Barbara; maybe in a few years when husbands, children, and parents find they’re still burying their "cured" loved ones.