Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

A Merck-y Business, The Case against Mandatory HPV Vaccinations

February 02, 2007 · Michael Fumento · The Weekly Standard · Disease Legislators in some 20 states are considering making mandatory Merck & Co.’s

Gardasil vaccination for the human papillomavirus. In Texas, Republican

governor Rick Perry bypassed the legislature and ordered it on his own. The

requirement there applies to 11- and 12-year-old girls entering 6th grade.

Legislators in some 20 states are considering making mandatory Merck & Co.’s

Gardasil vaccination for the human papillomavirus. In Texas, Republican

governor Rick Perry bypassed the legislature and ordered it on his own. The

requirement there applies to 11- and 12-year-old girls entering 6th grade.

The benefits seem clear. FDA-approved for females age 9 to 26, the vaccine has been shown to be 100 percent effective at preventing disease from the two HPV strains that account for 70 percent of all cervical cancers. Government estimates are that there will be 11,150 cases and 3,670 deaths from cervical cancer in 2007. So what’s not to like?

Plenty.

One argument is that a mandate removes parental authority. Which it does, but so do all mandatory vaccinations. The difference here is that while Perry claims the HPV vaccine is no different from the polio vaccine, polio is transmitted through the breath, while HPV is transmitted by sexual intercourse.

As Robert Zavoski, physician and president of the Connecticut chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, explained to the Hartford Courant, "Vaccines previously mandated for universal use are those which protect the public’s health against agents easily communicated, responsible for epidemics, or causing significant morbidity or mortality among those passively exposed to the illness." He added, "HPV is not an agent of this sort."

Sorry, but there’s no powerful biological urge to step on a rusty nail.

The other argument, which many Christian groups have made in addition to the one about parental authority, is that a mandatory vaccination will encourage promiscuity. This idea has been mocked. District of Columbia councilman David Catania, sponsor of a mandatory HPV vaccine bill, for example, insists, "This vaccine no more encourages sexual activity than a tetanus shot encourages you to step on a rusty nail."

But again, the analogy is faulty. There is no biological urge to step on rusty nails. There is, however, a powerful urge to have sexual intercourse that begins at puberty. It’s an urge that nations and religions throughout history have sought to control in various ways because sexual intercourse, while pleasurable to the participants at the time, can have consequences that are deleterious to the individuals later as well as to society as a whole.

When you insist that 11-year-old girls receive shots to protect them from dangers attending sexual intercourse, you are sending them a message. In fact, you’re even sending their male peers a message. And it is one that conflicts with the message that sexual activity is best left to people who are more mature.

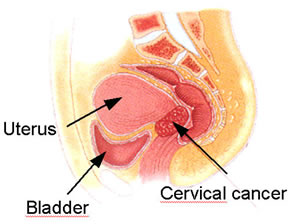

Pap smear diagram

Still, what about those preventable infections and cancers? HPV infection is usually fairly benign; in fact, a study just released by the CDC says about 27 percent of U.S. females aged 14 to 59 years have it. Importantly, only 2.2 percent of those women are carrying one of the two virus strains most likely to lead to cervical cancer. Usually infection is asymptomatic; but in a minority of cases it leads to tiny cauliflower-like bumps on the genitalia (or anus) that will disappear on their own or be zapped off by a doctor. And in a much smaller minority of cases, infection leads to cell irregularities that become cervical cancer.

The 3,670 deaths from cervical cancer expected this year are a tiny fraction of the 270,100 projected female deaths from all cancers. Further, both the incidence and the death rate for cervical cancer are dropping. The incidence was 14.8 per 100,000 women in 1973 according to federal data, but down to 7.1 per 100,000 by 2003. Meanwhile, the incidence of cancer generally increased. "Cervical cancer was the only cancer among the top 15 cancers that decreased in women of all races and ethnicities," according to the American Cancer Society. Cervical cancer death rates declined steadily from 5.6 per 100,000 in 1975 to 2.5 in 2003.

The main reason for the declines in both incidence and death is the Pap test or Pap smear. Public health campaigns and individual physicians have sought to convince women to get these tests, in which tiny samples are scraped from the opening of the cervix. Moreover, computer imaging has improved the reading of these smears, leading to fewer false results. Early treatment has also improved, with the use of a laser to vaporize cells showing abnormal growth.

Pap smears are not 100 percent effective at finding cells before they become cancerous, but they have the added benefit of detecting pre-cancerous cells with causes other than HPV. These include other sexually transmitted diseases. Remember, too, that Gardasil prevents only 70 percent of HPV infections that lead to cervical cancer. Thus, even women who have been vaccinated must still be encouraged to get Pap smears every three years.

Yet if the Gardasil inoculation sends a message about intercourse, it also sends a much stronger message about Pap smears. Why bother when one is already protected (mostly) from the big danger, cervical cancer? Psychology must be considered as well as physiology.

The usefulness of detection programs is enhanced by the long latency time from HPV infection to cancer. According to physician Mark Spitzer, a gynecologist at New York Methodist Hospital, in a small minority of women, "viral persistence may result in the development of a carcinoma in situ lesion [remaining within the cervix] about 8 or 9 years later. The transition from carcinoma in situ to microinvasive cancer takes a long time, since the median age of microinvasive cancer is approximately 41, or about 12 years older than carcinoma in situ. The median age of [potentially lethal] invasive carcinoma is not for another 7 years after that."

If enough mandatory vaccination laws are passed, this will be liquid gold for Merck.

Do the math. After an initial latency period of, say, 8 months (but possibly "many years or decades"), add an additional 8 years, plus 12 more years, plus 7 more years before we have a life-threatening, invasive carcinoma – 28 years total. That’s why the age bracket with the highest rate of death from cervical cancer is 45-54 and the second highest is 55-64. HPV is generally a young woman’s disease; cervical cancer generally that of older women. Averages, of course, are just that. Some will develop the cancer sooner and others later. But once you realize we’re talking about an almost three-decade-long period that doesn’t begin until the woman first has intercourse and becomes infected, the speed with which politicians are trying to foist these mandates upon parents seems unwarranted.

Indeed, cervical cancer could conceivably be a thing of the past before today’s young vaccine candidates reach middle age. As computers become more powerful – with developments such as Intel’s "teraflop chip," Hewlett-Packard’s nano-chip, and even quantum computing – drug and biologic testing will be transformed, made vastly faster and more effective. Yet as long ago as 1999, a CDC representative testified before Congress that with then-current medical technology and heightened awareness of the need for Pap smears, cervical cancer was "nearly 100 percent preventable."

So why such urgency on the part of lawmakers? Maybe it reflects urgency on the part of Gardasil’s maker, Merck & Co. Last December, at a briefing on Wall Street, the president of global human health at Merck, Peter Loescher, remarked that he stresses "speed, speed, speed" in a product launch. That may be because another HPV vaccine, Cervarix from GlaxoSmithKline, was submitted to the European Union for approval about a year ago, and GSK is expected to submit it to the FDA this year.

Moreover, in January GSK announced a head-to-head clinical trial against Gardasil, indicating it believes it may have a superior product. In any event, Cervarix would certainly cut into the profit margin of Merck’s vaccine, which, at $360 for the series of three inoculations, is the most expensive vaccine available.

To that end, "Merck is bankrolling efforts to pass state laws across the country," according to the Associated Press. The Baltimore Sun was the first to report that Women in Government, a national advocacy group of female state legislators that’s been lobbying hard for mandatory Gardasil vaccinations, has been taking Merck money. "In addition to vaccination mandates, Merck supports measures that would require private insurers and Medicaid to cover the cost of the vaccine," said the Sun. The paper also relayed the estimates of Wall Street analysts: "The vaccine is expected to reach $1 billion in sales next year, and state mandates could make Gardasil a mega-blockbuster drug within five years, with sales of more than $4 billion."

The AP meanwhile reported it obtained documents showing Gov. Perry’s chief of staff met with key aides about Gardasil the same day its manufacturer donated money to Perry’s campaign. That day, Merck’s political action committee forked over $5,000 to Perry and $5,000 total to eight state lawmakers.

"It’s not the vaccine community pushing for this," physician Martin Myers, director of the National Network for Immunization Information, told the Sun. Myers, former head of the federal National Vaccine Program Office, added, "Many of us are concerned a mandate may be premature, and it’s important for people to realize that this isn’t as clear-cut as with some previous vaccines."

Finally, in the face of all this bad publicity, Merck announced it would stop lobbying for mandatory vaccination.

The Third World has almost all the cervical cancer deaths and Pap smears are rarely available. That’s where the Merck vaccine needs to go.

In any event, the real need for an HPV vaccine is outside the United States. According to the World Health Organization, cervical cancer worldwide strikes half a million women yearly and kills 250,000 of them. In developing countries it is the greatest cause of cancer deaths in women. There, neither incidence nor death rates are falling.

WHO has also found that "cervical cancer screening programs in [Latin America and the Caribbean] have generally failed to reduce cases and mortality rates largely because of inadequacies in treatment and follow-up." That’s where these vaccines need to go, with support from such philanthropies as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Obviously, though, the price will have to come way down from that $360.

None of this is to deny that HPV vaccines have the potential to save lives and possibly also money in the U.S. market – though cost considerations must take into account that under a mandatory program, we are shelling out $360 per vaccine for tens of millions of people.

This is not to say these vaccines shouldn’t continue to be available to women and parents who feel they can afford them. It is to say we can afford to wait for Merck to receive some healthy competition. Nor should the concerns of those worried about both the loss of parental control and the encouragement of early sexual intercourse be dismissed so lightly.