Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Constipated Colombia Pact And The Missing Massacre

March 14, 2011 · Michael Fumento · Economy

Even by Latin American standards, Colombia's economy is booming.

Sometimes it takes a bit of legal political extortion to get politicians to do the right thing, even the very thing they’ve claimed they want to do. Such was the case with breaking the shackles President Obama and the Democratic Party clamped on the Colombia Free Trade Agreement at the behest of Big Labor.

Obama has made expanding U.S. exports a centerpiece of his economic plan. In his January State of the Union address , he announced the goal of doubling American exports of goods and services in five years, noting that "95% of the world’s customers and fastest-growing markets are beyond our borders" and that export-related jobs "pay 15% more than average." At a time when jobs are in short supply, he later said, "building exports is an imperative."

Erasing Tariffs

The Colombia deal was made to order. It’s heavily lopsided toward the U.S. because Colombia’s exports to us are already tariff-free, while our products sent there carry duties of up to 25% — an estimated $3.2 billion total since the agreement was reached.

Those tariffs would disappear and, according to the U.S. International Trade Commission, expand opportunities for a broad array of U.S. sectors , increase our gross domestic product by about $2.5 billion , lower our massive trade deficit and create J-O-B-S.

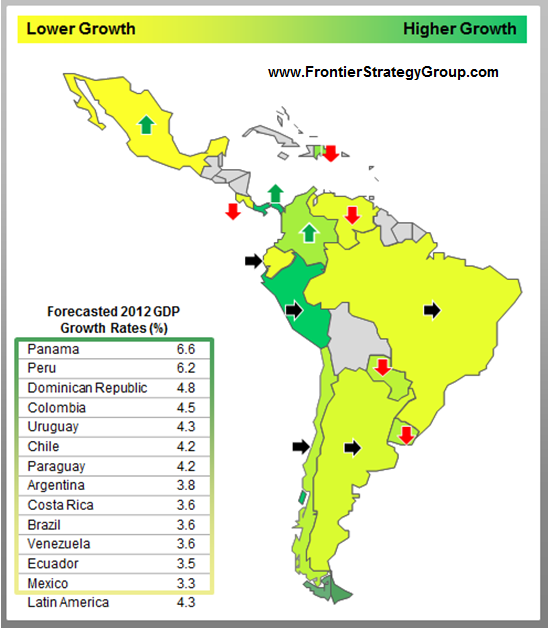

Way down south is exactly where export markets are opening up. Economic performance confidence levels are higher in Latin America than in any other part of the world, according to Thornton International’s recent report. That’s why other nations are busily entering trade agreements with Colombia , including the entire European Union .

And, as the American Farm Bureau’s Chris Garza explained to me, late-comers really get whacked, because once two companies make an international agreement, breaking that bond can be really tough.

Colombia also has the third-largest population in Latin America, enjoys real GDP growth twice that of Mexico and vastly higher than U.S. levels , and has made incredible progress combating both narcotics trafficking and a 50-year-old guerrilla movement .

I have seen the future; in two months I’m moving to Medellin, once considered the world’s most dangerous city.

Protectionism, Anyone?

Yet when President Bush sent the pact to Congress in 2008 , the Democratic leadership made great haste to do nothing with it. That’s because Big Labor doesn’t want to compete. And in the last two decades, labor unions have contributed more than two-thirds of a billion dollars to election campaigns — with over 90% going to Democrats.

Of course, nobody is going to say old-fashioned protectionism is at work. What they invented is that "Congress can’t take up an agreement with Colombia until the horrific violence and labor-rights record are addressed."

So said Rep. Mike Michaud , D-Maine, co-founder of the House Trade Working Group, who coincidentally also vowed to fight a free-trade pact with South Korea , concluded in early December, citing entirely different reasons.

"In Colombia, joining a union or advocating for workers’ rights can be a de facto death sentence," declared John Sweeney , former president of the AFL-CIO. We’re also told that somehow a nation with a mere 0.6% of the world’s population has more union members murdered "than the rest of the world combined every year."

In fact:

- Last year, 28 Colombian labor union members were killed, according to the U.N.’s International Labor Organization (ILO). That’s out of 1.5 million members . New Orleans in 2009 had 173 murders out of only 342,000 people.

- The murder rate for Colombian union members is vastly below that of the overall population, and yet even that rate has dropped 60% from its height in 1991 .

- The latest ILO report lists 25 nations to be scrutinized for failure to comply with international workers’ conditions. Guess what nation isn’t on it?

- Colombian union membership has almost doubled in the last few years.

I’ve been there, kid. And I’ve read outsiders’ reports. They have them.

After the political equation changed in November, another tactic was needed. So in December, just after announcing that the Korean agreement would go to Congress, the White House peered into its crystal ball and said the Colombia one would not because "it doesn’t have the votes ."

Ay caramba! "The votes for Colombia are here today," then-incoming chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee Kevin Brady, R-Texas , told me at the time. "We are not going to let that agreement fall along the wayside." When it became clear Brady meant it, the administration changed its tune — though not its actions.

The president said he supported ratifying the Colombian pact, as well as one with Panama signed in 1997. But where the Korean pact was deemed good to go, the Latin ones were put in the slow lane — ostensibly to be completed sometime this year.

No deal, said Brady, who along with the rest of the Senate GOP declared that until all three pacts went to Congress, Obama’s nomination of a new commerce secretary would also be on permanent hold.

It worked. President Obama was to meet with the Colombian president Thursday to make a few changes in the deal before sending it to Congress. Those changes would concern — yes — trade union violence in Colombia.

Ah well. Whatever it takes.