Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Splice of Life

December 09, 2002 · Michael Fumento · Tech Central Station · Biotech

It made page one of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. Yet it had nothing to do with terrorism, Iraq, nor even American Idol.

Instead it was a vaccine made by splicing a protein into what makes bread rise, yeast. But what’s going to rise dramatically with this development are life expectancies both here and especially in parts of the world already wracked by disease. This vaccine has the potential to prevent – not just cure or treat – over a quarter million female deaths a year. Much more than that, it’s a harbinger of the wonders that await us with biotech vaccines.

Developed by the pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co., Inc. of Whitehouse Station, New Jersey, the vaccine actually contains four different antigens – proteins that provoke the immune system into creating protective antibodies. (The study in the New England Journal of Medicine [NEJM] that sparked the furor concerned an earlier version with only one antigen.) All four protect against different strains of the most common sexually transmitted disease (STD), the human papillomavirus virus (HPV).

Two of the strains, labeled HPV 6 and 11, cause unsightly genital warts in both men and women. But the other two, HPV 16 and 18, are thought to cause about 70 percent of all cases of cervical cancer.

In the U.S., regular pap smears have caused a dramatic 30-year decline in full-blown cervical cancer cases and resulting deaths, so that only about 4,100 American women die of the disease annually now. But this prevention is terribly expensive, costing about $3 billion annually for the smears, follow-up biopsies on women with abnormal findings, and for other services associated with HPV infection. An effective vaccine would eliminate most of that expense.

Far more important, however, is that most countries can’t afford such preventative care. As a result, cervical cancer killed almost 260,000 women last year according to the World Health Organization. After breast cancer, it’s the world’s second greatest cause of female cancer deaths.

Judged only by what it may directly accomplish, this vaccine could be a tremendous breakthrough. Yet considering its attributes, the potential goes far beyond its purpose.

Consider, for one, that it’s only the second vaccine that can actually prevent cancer. The first was the original vaccine developed against hepatitis B, which often leads to cancer of the liver. Like the HPV vaccine, that for hepatitis B (also from Merck) is made from gene-spliced yeast.

Further, the HPV vaccine would be the first to protect against STDs. "Years ago people did not believe that you could actually prevent an infection of the genital track," Merck’s team leader Dr. Kathrin Jansen told me. "I always believed it could work, but there was a lot of resistance."

That said, the same issue of the NEJM that carried the Merck’s HPV study also reported a major advance by GlaxoSmithKline in developing a vaccine that protects against genital herpes. By no coincidence, it, too, is recombinant.

Another stunning feature of the Merck vaccine is that out of about 1,200 women who received it, the protection rate was 100 percent. That doesn’t mean the vaccine is "100 percent effective," as you may have read. Surely it won’t be when given to hundreds of millions of women, each with their own unique genetic make-up and some of whom would have immune systems compromised by AIDS and other diseases. But such a high protection rate in such a large clinical trial is what is known in strictly scientific terms as "awfully damned good."

Future Looks Bright

For all this, what’s most important about the Merck vaccine is that it’s the wave of the future. Traditionally, vaccines have come in two forms: Live but weakened, or killed. Both have pros and cons. Live vaccines usually confer longer and stronger immunity but sometimes produce the disease itself. Recombinants offer the best of both worlds by taking merely one gene or a few genes from a virus, splicing them into another organism, and replicating them.

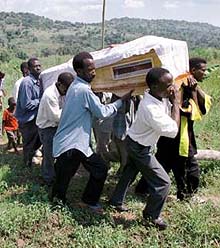

Cervical cancer kills about a quarter million women each year, most in the developing countries where pap smears aren’t affordable.

"HPV can’t be grown in tissue cultures like other attenuated [live] viruses used for other vaccines," explains Frank Taddeo, a colleague of Dr. Jansen. "Growing it in yeast allows you to get a highly purified product." That’s important, he says, because it’s those very impurities that can cause side effects.

Back in 1986 when the hepatitis B vaccine was introduced, the idea of recombinant vaccines was so new that Merck actually named it "Recombivax HB." Today that would be like Ford naming a new vehicle "The SUV."

Today, about 100 biotech vaccines are under development. Researchers are working on recombinant vaccines to combat influenza, AIDS, plague, allergies, fungal infections, cholera, and other diarrheal diseases ranging from those causing mild discomfort to those that kill. There’s now a recombinant vaccine that protects against both hepatitis A and B. The only approved vaccine for Lyme disease, spread by ticks, is recombinant. Researchers are developing a biotech vaccine against staph germs, which are the top cause of illness in hospitals.

Although the Ebola virus is severely hyped, having spawned far more scary articles, books, and movies than actual victims, its fierce reputation may soon be tamed by a recombinant vaccine that has successfully protected laboratory monkeys. Other targets within biotech’s gun sights for which there are currently no vaccines include hepatitis C, West Nile Virus, and malaria (see "Biotech Bullets").

Biotech vaccines will also be weapons in the war on terrorism. The current anthrax vaccine requires six injections over 18 months, plus an annual booster. A recombinant one scheduled to begin safety testing next year would confer immunity with only three injections.

Yes, we’ve all heard of those spine-tingling doomsayer books in which germs take over the world, such as Laurie Garrett’s The Coming Plague. But the thrills in Harry Potter are more realistic. Germs are going to lose, and nothing will do more to ensure that than biotech vaccines.