Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Out of Touch

January 01, 2004 · Michael Fumento · Citizen Magazine · BiotechPresident George W. Bush has taken a lot of heat for his stand against funding future embryonic stem-cell (ESC) research – not only from the media and Congress, but from some of America’s most beloved stars.

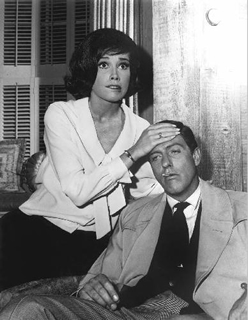

Mary Tyler Moore is a caring person, but there’s no evidence she’s even heard of an adult stem cell.

Mary Tyler Moore, for example, appeared before Congress this spring to provide celebrity support for a letter to President Bush from 206 congressmen (including some conservatives) calling on him to reverse his policy. This wasn’t the first time Moore, who suffers from juvenile-onset diabetes, has taken the spotlight on this issue. In 2001, she told Congress that "studies have shown that when the issue is explained clearly, up to 71 percent of the American public would approve federal funding of ESC research to cure diabetes, Parkinson’s and other diseases."

Unfortunately, the actress best known for playing a news producer hasn’t kept up with the news in science. Nor have those 206 members of Congress. If the issue were explained clearly, the American public would almost certainly oppose expanded funding. Instead, they would favor an alternative called adult stem cells (ASCs).

Despite their name, "adult" stem cells actually are found in a variety of tissues in all humans of all ages, and are also plentiful in umbilical-cord blood and placentas. ESCs, on the other hand, are obtained by taking apart human embryos that are either left over from in-vitro fertilization attempts or grown specifically for that purpose. That leaves even many people who aren’t strong pro-lifers uneasy and inclined to prefer another alternative.

That’s where ASCs come in. Further, ESC research contributes to human cloning insofar as both are identical right up to the point of implantation into the womb. If human cloning bothers you, ESC research should, too.

No Contest

Currently, no medical therapies involve ESCs, nor is there a single human trial using them. Indeed, very few have even made it to animal testing. Yet ASCs have been routinely used to treat human disease since the 1980s. Since then, scientists have learned to culture and grow ASCs outside the body and convert them into an incredible array of human tissue. Ever hear of a bone-marrow transplant or umbilical-cord blood transplant? It’s not the marrow or the blood that’s key – it’s the stem cells contained therein.

"Adult stem cells are like babies who, when they grow up, can enter a variety of professions," explained Dr. Marc Hedrick of the UCLA School of Medicine. They "can become many tissues by making certain changes in their environment."

Originally, use of ASCs was limited to injecting them into the body, where they theoretically would rush to the place they were needed and automatically perform repairs. But now scientists can extract them and convert some of them into the desired tissue. Hedrick’s lab has made cells from liposuctioned fat into more fat (for cosmetic purposes), cartilage and muscle. Switzerland-based Modex Therapeutics sells skin grown from stem cells found in human hair follicles that are in every way – including cost – superior to standard skin grafts used for burn patients and those with nonhealing sores.

In addition to being such latecomers, ESCs have other drawbacks – like a nasty tendency, once implanted, to keep growing and become cancerous in certain situations. They also are usually rejected by the recipient’s immune system. By contrast, ASCs are less likely to become cancerous, are obviously not rejected when taken from the patient’s own body, and in fact, apparently are rejected less often even when transferred from one human to another.

If ESCs have any advantage, it’s clearly not in terms of established usage but of potential. But do they even have that?

It was long believed that an ESC could become absolutely any cell in the body, whereas each type of ASC could only differentiate into a cell within its own germ layer – that is, the digestive, circulatory or nervous system. In fact, there is no proof that ESCs can be manipulated to become all types of cells. As to the alleged restriction on ASCs, who says we need a "one-size-fits-all" cell? ASCs have been discovered throughout the body and in all three types of germ-cell categories. It could be that just the ASCs we already know of (much less those we’ve yet to discover) can be made into the more than 200 different types of cells in the body.

Moreover, there’s mounting evidence that ASCs may be far more versatile than once thought. In the July 2002 issue of Nature, Catherine Verfaillie and her colleagues at the University of Minnesota’s Stem Cell Institute reported they’d found stem cells in human marrow with apparent potential to form all three of the embryonic germ layers. (They’ve got "basically all the benefits of ES cells and none of the drawbacks," said Dr. David Hess, a neurologist at the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta.) Verfaillie has isolated them from mice, rats and people. They’ve already been transformed into cells of blood, gut, liver, lung, brain and other organs. Since then, two additional sets of researchers have found two separate types of ASCs that may also be as versatile as ESCs – further supporting Verfaillie’s findings.

The Need to Feed

Because private investors are wisely investing in adult stem cells, labs using embryonic ones need to feed at the federal trough.

So why all the incredible pressure on the Bush administration to open the federal spigot for ESC experimentation?

It’s precisely because ASCs are superior, and private investors know it. Hence they plow their money into ASC research. Starved for funding, ESC researchers – who operated for years under the false belief that their path held more promise – may find their hopes dashed. They need to feed at the federal trough. So they’ve waged a high-profile disinformation campaign to exaggerate any possible ESC development, even as they pooh-pooh or ignore all ASC breakthroughs.

The media, convinced that the debate is between religious zealots on one side and scientists on the other, are crucial to the ploy. Time and again, astonishing ASC research is simply referred to as "stem cell," whereas any potential advance with ESCs is carefully identified as such. Influential science journals such as Science and Nature have repeatedly published utterly nonsensical attacks on ASC research.

Thus Nature, in March of 2002, printed two lengthy letters regarding petri-dish studies claiming that stem cells might not be growing at all, but merely fusing together. It was akin to saying that people get in steel tubes in Los Angeles and end up a few hours later in New York, but there’s no evidence the tubes can actually fly.

Yet, the media gobbled it up. " ’Breakthrough’ in Adult Stem Cells Is Hype, Studies Warn," headlined the Agence-Presse France news service. "New Research Tips Debate on Stem Cells," insisted the Australian Associated Press. "Adult Cells Found Less Useful than Embryonic Ones," claimed The Washington Post.

Many scientists are dismayed at such bias and ignorance. British researchers editorialized in the February 2003 Journal of Cell Science that "despite such irrefutable evidence of what is possible, a veritable chorus of detractors of adult-stem cell plasticity has emerged, some doubting its very existence, motivated perhaps by more than a little self-interest."

Moral problems with ESCs aside, the money problems remain. The federal research funding pie is limited, and huge chunks already go to politically correct causes such as AIDS. And while the National Institutes of Health (NIH) certainly can distinguish between real science and hype, to the extent that the public and Congress (holder of NIH’s purse strings) are convinced that ASCs are worthless and ESCs have tremendous promise, money will flow to the ESC research.

"Everybody is fighting over the same pie, and there’s a lot of pressure on NIH to give these scientists [working with embryonic cells] what they want," Hess said.

The ASCs’ amazing ability and the failures and snail’s-pace progress of ESCs are perhaps the best-kept secret since KFC’s "blend of seven herbs and spices." Maybe if the public knew more about them, they’d demand that not a dime of federal money be spent on highly speculative research that not only do many taxpayers find morally repugnant, but that also steals funds from other scientific endeavors with longer records and far greater promise of improving and saving lives.