Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

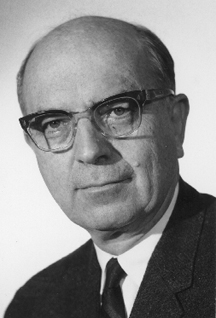

Alexander Langmuir

January 01, 2000 · Michael Fumento · Investo's Business Daily, Inc. · AidsIt’s part of American folk lore: The man who saves the day and rides off into the sunset without anybody knowing his name. Sometimes he doesn’t even leave a silver bullet.

Dr. Alexander Langmuir, the father of infectious disease epidemiology, was such a man.

Langmuir died last month of kidney cancer at the age of 83.

"He had an absolutely profound impact on saving lives," said Alan Summer, Dean of the Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health and a former student of Langmuir’s. "If one wants to include important roles he played, the people he trained and what they’ve gone on to do, a figure in the millions (of lives saved) would certainly be true."

Epidemiology is the science of trying to connect disease or injury with a cause. By doing so, it is often possible to eliminate that cause.

In 1949, Langmuir created the epidemiology section at what is now known as the Federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. He had been called upon to combat a perceived epidemic of malaria but discovered that there wasn’t one.

Al Langmuir

Langmuir was also quite critical of what has been described as America’s "risk of the week" syndrome. Commenting on the cellular phone brain tumor scare earlier this year, he told Investor’s Business Daily, "It’s perfectly god awful. It’s totally irrational."

But Langmuir took advantage of the situation by using the money to set up an organization to fight real epidemics. This became the Epidemic Intelligence Service.

"Langmuir had a broader idea of what this should be," said Henderson. It should be "a backup to the states, a resource that should be drawn on from whatever problems would emerge."

"By creating this concept of surveillance and disease reporting, of having a whole group of physicians on call as we were 24 hours a day, and if there was an epidemic you would drop everything to go immediately and help states," he added.

After the Korean War broke out in 1950, Langmuir again sensed opportunity and tapped into the supply of medical personnel being recalled to duty. He kept them stateside, teaching them the principles of what would later be called shoe-leather epidemiology.

This comprised accurate, comprehensive surveillance combined with sending doctors out into the field to interview victims, their families, local officials, and anyone who could provide information concerning local outbreaks.

The rolls of the EIS now read like a Who’s Who of the medical profession, including surgeon generals, CDC heads, the last head of the Public Health Service, the current director of the World Health Organization’s AIDS program, and many deans of the country’s 20 schools of public health.

"Almost like a professor in a university," said Henderson, "he worked with each of the EIS officers, challenging them, ensuring the integrity of their studies, querying them. All of these things resulted in a great many people ending up in public health who would never have done so."

One example is Henderson himself, who headed up the world’s most successful attempt to control a disease - the World Health Organization’s program to eradicate smallpox.

Prior to the campaign, the disease was killing two and a half million people a year, and disfigured many more. Henderson says the real credit for the eradication should go to Langmuir.

"He emphasized surveillance with regard to disease wherever it occurred, analyzing it and looking at it, and acting if appropriate," Henderson said. "That’s what we did with smallpox eradication. It was basically Langmuirian principles."

He says those same principles are now being applied in the attempt to eliminate other dread diseases, including the polio eradication effort that has so far succeeded in wiping out the disease in Western countries.

"In my own area, I discovered that mild Vitamin A deficiency is probably responsible for one to three million children dying or going blind each year," Summers said. "It is now the big international activity that UNICEF and other organizations have identified as a critical issue and have resolved to control by the year 2000."

The emergency investigative service Langmuir established at the CDC also continues to fly to disease outbreaks at a moment’s notice.

When attendees at an American Legion conference suddenly began dying, it was the CDC that found the cause. Likewise, when young homosexual men in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco began succumbing to a strange new illness, it was the CDC that interviewed thousands and discovered the means of transmitting what would become known as AIDS.

While Langmuir set up the apparatus to deal with real epidemics, he also exposed those that have been exaggerated.

After the introduction of the Salk polio vaccine in the mid-1950s, reports of persons developing the disease from the inoculation sent the nation into a panic and threatened the program.

Langmuir had the CDC investigate each case and found that primarily one company was involved.

"He predicted that there would eventually be 120 cases and there turned out to be 122," Henderson said. "The process was corrected and we went ahead with vaccinations."

In recent years, Langmuir became critical of the CDC’s handling of AIDS. He believed that the organization was overstating both the overall numbers of infected individuals and especially the risk to non-drug-abusing heterosexuals of contracting the disease.

Langmuir hated false epidemics, such as that involving cell phones and brain tumors.

Langmuir was also quite critical of what has been described as America’s "risk of the week" syndrome. Commenting on the cellular phone brain tumor scare earlier this year, he told Investor’s Business Daily, "It’s perfectly god awful. It’s totally irrational."

Langmuir was the CDC’s chief epidemiologist from 1949 to 1970. He spent the rest of his life teaching at Harvard Medical School and at Johns Hopkins, from which he had earned his degree in public health.

"As a teacher he was incredible. He could really capture an audience in ways that was difficult to describe," said Dr. Jonathan Freeman, a professor of epidemiology who taught with Langmuir at Harvard. Earlier this year, Langmuir received an award from his students at Johns Hopkins for being an outstanding instructor.

"You could always see in this man tremendous vision," said Henderson. "When you look back, you see this is one of those people who has very profoundly affected an entire field and a generation through sheer personality, and his ability to teach and inspire."