Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Vietnam Flashback

January 01, 2000 · Michael Fumento · Reason · AgentU.S. veterans groups have long considered Agent Orange, the controversial herbicide used to defoliate jungles during the Vietnam War, a bigger villain than Ho Chi Minh and Henry Kissinger combined. Agent Orange exposure has been blamed for virtually any disease Vietnam vets and their offspring have ever suffered since the soldiers finished their tours of duty. These include everything from recurring rashes, dizziness, nausea, migraine headaches, stomach aches, and clinical depression to a plethora of cancers and birth defects.

Some would have us think Uncle Ho was a good guy compared to those who ordered the Agent Orange spraying.

Congress and the Department of Veterans Affairs have responded with two official presumptions. First, that all Vietnam vets had Agent Orange exposure, even though blood testing has shown that only a handful had any exposure. Second, that certain cancers and one type of severe birth defect, spina bifida, are caused by the presumptive exposure.

Never mind that studies in both the United States (by the Centers for Disease Control) and Australia found that the children of Vietnam vets had as few or fewer birth defects than the general population. Another CDC study found that one type of cancer was abnormally prevalent among vets, but only among sailors who served on ships off the coast and hence couldn’t have been exposed to the defoliant. Miscarriage studies also have found no significant increase among vets or their spouses. Agent Orange has been cleared by every serious scientific study.

Until, it seems, now. Air Force researchers think they’ve finally, unquestionably pinned a disease on Agent Orange. Or so major media coverage of the study would indicate. The headlines in late March were unequivocal:

- "Study Finds Strong Link Between Vietnam War Herbicide and Diabetes" (Associated Press)

- "Air Force Study Finds Strong Link Between Exposure to Agent Orange and Diabetes" (CBS Evening News)

- "Agent Orange Harmful" (ABC’s World News Tonight)

- "Vets Say VA Must Act on Agent Orange-Diabetes Link" (Copley News Service)

As Dr. Joel Michalek, head of the Air Force research team, said at a press conference: "This report includes the strongest evidence...that exposure to Agent Orange is associated with adult-onset diabetes."

Instead of a ribbon, Agent Orange has its own flag . . .

But the implications of the headlines, and Michalek’s statement, are wrong. And the proof can be readily found in the introduction and conclusion of the 1,700-page report itself, which was available on the Web.

While the report doesn’t support claims that Agent Orange causes diabetes, its media treatment is an object lesson in how weak science gets used for political purposes — and how those who should know better needlessly spread fear and anxiety. How the Agent Orange story has been spread is emblematic of other war "syndromes," including Gulf War Syndrome, and even something called "Korea Vet Early Death Syndrome," which may be catching on in Canada (but has yet to invade the U.S.).

The Air Force study is based on exhaustive health evaluations performed every five years since 1982 on veterans of Operation Ranch Hand, the Air Force operation that sprayed 90 percent of all the Agent Orange herbicide used in Vietnam. Many Ranch Hand veterans still have elevated levels of dioxin — a contaminant always present in the herbicide — in their bodies as a result of their long-ago exposures. For anyone interested in the possible health effects of Agent Orange and dioxin, it makes sense to examine the men with the highest exposures. If you don’t find health problems in them, there’s no reason to expect problems in persons with barely detectable or wholly undetectable exposures.

. . . and its own patch.

The latest examination results, based on 1997-98 examinations just now emerging from the long pipe of scientific report-writing, found that Ranch Hands had no more adult-onset diabetes than vets who flew the same types of aircraft in Southeast Asia but didn’t spray any herbicides, be it Agent Orange or something else. But the 238 Ranch Hands with the highest dioxin levels in their blood (more than 10 parts per trillion) were 47 percent more likely to have diabetes than those 232 Ranch Hands with the lowest dioxin levels.

That’s all the evidence for the diabetes-Agent Orange connection — and it’s not the kind of evidence any district attorney would want to go to court with. First, as the report itself notes (on page 19-9), the 47 percent increase was not statistically significant. "Statistical significance" is a term epidemiologists use to describe whether an increase or decrease falls outside the bounds of what could be expected by chance. Scientists sometimes find 1,000 percent increases of some risk or other, but if few enough people were included in the study, they can’t reliably conclude that such apparently huge risk elevations weren’t merely random chance.

Yet even if the 47 percent increase (which epidemiologists refer to as a "relative risk" of 1.47) was statistically significant, it wouldn’t mean much. Says who? The authors of the Air Force report (on page 1-10): "Statistically significant relative risks less than 2.0 are generally considered to be less important than larger risks because relative risks less than 2.0 can arise more easily because of unrecognized bias or confounding." Bias and confounding variables are possible contributing factors which epidemiologists might not have been able to keep out of their data that confuse results. Dietary habits are a common one, for example, though in this study the Air Force authors took such matters as the amount of fruits, vegetables, and fats in the vets’ diets into account.

Planes defoliating the jungles of South Vietnam and deny the enemy cover.

But there’s a result of dietary habits that may well have influenced the results. That particular confounder was the whole reason the Ranch Hand study could even be done. Dioxin, the marker for Agent Orange exposure decades ago, is stored in body fat and works its way out into the bloodstream so slowly that it can be measured many years later. Fatter people don’t release fat-soluble compounds like dioxin nearly as quickly as thinner people, notes Michael Gough, a biologist who was chairman of a federal advisory panel for the Ranch Hand study from 1990 to 1995. Thus, higher dioxin levels are associated with higher obesity levels. And what’s one of the main risk factors for adult-onset diabetes? Obesity. "It’s far less likely that Agent Orange is the cause of the diabetes than is obesity," says Gough.

Dr. Michalek, the Air Force project leader, himself told New York Times science writer Gina Kolata, "We know diabetes is highly related to body fat, and so is dioxin. That’s why these diabetes findings are so difficult to interpret. People are concerned that we haven’t done the right body fat adjustment."

Kolata, my Nexis searches indicate, appears to be the only reporter who voiced the least bit of skepticism about the Agent Orange-diabetes "connection." Her very headline did not refer to any diabetes "link" or "connection" but merely said, "Agent Orange and Diabetes: Diving into Murky Depths." Unfortunately, the Times’ main article on the study was written not by any of the paper’s excellent science writers but by its military reporter. Military reporters specialize in areas more or less exclusive to the military, such as equipment, needs of personnel, tactics, and strategy. They are not expected to, and as a general rule do not have, any background or expertise in medicine, nor even names in a Rolodex to help them out.

None of this is to dispute Michalek’s claim that his report is the "strongest evidence" of an Agent Orange link to diabetes. He’s absolutely right about that. It is the strongest evidence, which actually speaks volumes about its weakness. For example, notes Gough, "There have been several large studies of chemical plant workers in the U.S. and Europe exposed to huge levels of dioxin and the components of Agent Orange. None of these studies have found excesses of diabetes."

Veterans Affairs now pays compensation to Vietnam veterans who develop any of several "Agent Orange-related diseases." It’s a virtual given that the current clamor from veterans groups and politicians will convince the VA to add diabetes to that list. "Based on the evidence we have seen, the VA should make a decision that diabetes is presumed to be service-connected based on Agent Orange exposure," says John Sommer, executive director of the Washington office of the American Legion.

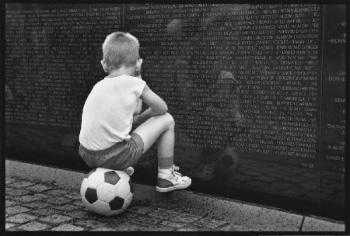

By taking the jungle away from superb jungle fighters, Agent Orange kept a lot of names off this wall.

Sommer may want to think twice about using the report. Beyond diabetes rates, the Air Force study looked at the other "Agent Orange-associated diseases," including nine different cancers, for which groups like the American Legion had lobbied to get compensation. What did it find? "Ranch Hand enlisted ground crew, the occupation with the highest dioxin levels and, presumably, the highest herbicide exposure, exhibited a decreased prevalence" of cancer. The Ranch Hands got cancer about 21 percent less often than the comparison group of Vietnam vets who sprayed no herbicide at all.

Like the 47 percent increase in diabetes, that decrease is statistically insignificant. But if you want to follow the lead of those media types and politicians who tossed statistical significance to the four winds in the case of diabetes, you can conclude that Agent Orange and dioxin exposure reduce cancer risks.

That said, don’t expect to find dioxin capsules in the vitamin store next to shark cartilage. Do expect this latest report to become part of the lore surrounding Agent Orange. And while some vets will receive compensation they don’t deserve, many more who bravely served in Vietnam will simply live out their lives in fear that they are at elevated risk for diabetes or cancer. That’s not the kindest way to thank them for their service.