Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Cancer

January 01, 2003 · Michael Fumento · Scripps Howard News Service · Cancer

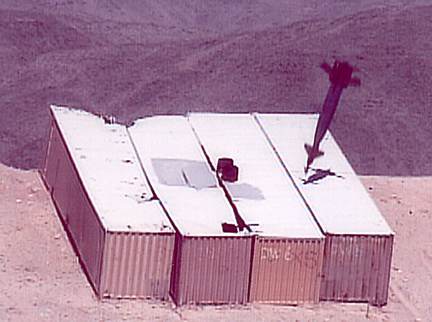

Tumor Angiogenesis (courtesy EntreMed)

"First we are going to cut it off and then we’re going to kill it."

That was Gen. Colin Powell’s winning plan in the 1991 Gulf War. An exciting method of attacking tumors fits Powell’s description exactly. Called "antiangiogenesis," it should soon become a powerful weapon against cancer.

Normally the body forms new blood vessels only during growth, repair and pregnancy. But it also does so with cancer, in a process called "angiogenesis." Once a tumor becomes the size of a small pea, it tells the body to produce chemicals that grow these vessels. They supply the tumor with oxygen and other nutrients necessary for survival and growth.

There are now more than 40 biotech antiangiogenic agents in various stages of oncology clinical trials that inhibit or outright block one or more of these vessel-growing chemicals, according to the Angiogenesis Foundation in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Antiangiogenic drugs can choke off even large tumors so they grow more slowly or even shrink or disappear.

Yet those same blood vessels play another diabolical role. They allow cells from tumor to enter the bloodstream, whence they travel throughout the body. This process is called metastasis. The immune system kills most of these free-floating mutant cells, but given time one will eventually take hold somewhere and sprout a new tumor.

Antiangiogenic drugs combat this by shutting down the blood vessels coming from the original tumor, as well as by preventing new tumors from sprouting their own vessels. "And it’s usually not the primary tumor that kills; it’s the metastasis," says president and medical director of the Angiogenesis Foundation Dr. William Li.

The principal of antiangiogenesis drugs has already been proved by available drugs, such as Pfizer’s Celebrex.

Developed as a pain reliever that’s gentle on the stomach, Celebrex later received FDA approval for treatment for pre-cancerous polyps of the colon and is now in human testing against a vast range of cancers.

Scientists have shown that Celebrex shuts down abnormal vessel growth. The first approved biotech antiangiogenic agents may be Genentech Inc.’s Avastin, and Aeterna Laboratories’ Neovastat.

Avastin was shown in Phase 3 of clinical trials (the final stage) to significantly improve survival in colorectal cancer patients when administered along with standard treatment. A Phase 3 trial of Neovastat showed it could double survival time in patients with the most common form of kidney cancer if the cancer had spread to only one site.

Antiangiogenic drugs zero in on tumors like a laser-guided bomb.

Antiangiogenesis is also exciting because it zeroes in on enemy blood vessels like a laser-guided bomb. Chemotherapy, conversely, carpet bombs dividing cells (including those in bone marrow) indiscriminately. This often sickens the patient, limiting both the dose and ultimately success of treatment.

Moreover, if the cancer is not eliminated entirely, some of the mutating cancer cells will become chemotherapy-resistant and the tumor comes roaring back. But blood vessels that feed these tumors do not mutate, so it appears they can be treated with antiangiogenic drugs indefinitely.

Antiangiogenic agents also appear to work against a huge array of cancers. A drug initially tested against breast cancer could prove equally, if not more effective, against prostate cancer or vice-versa.

Neovastat, for example, is in Phase 3 testing for lung cancer and has shown effectiveness in humans against the cancer multiple myeloma, prostate cancer, and even psoriasis. "We now know that angiogenesis is a common denominator in diseases long thought unrelated, including over 30 types of cancer," says Li.

Li points out that these aren’t just "solid tumors" like those of the breast, prostate, lung, or colon but "liquid" tumors as well, such as leukemia. These respond because liquid cancer cells are bathed in nutrients provided by blood vessels in the bone marrow.

Yet another advantage of antiangiogenesis drugs is that while they may be used instead of the traditional anti-cancer weapons of radiation, surgery and chemotherapy, they could also complement their use. Amazingly, angiogenesis inhibitors appear to "normalize" vessels before killing them. This can help anti-cancer agents reach tumors more effectively.

"The first generation (of antiangiostatins) in the pipeline now appears to have promise as monotherapy," says Dr. William Li. "But most experts believe they will be most useful when combined with standard therapies. The gold standard of oncology is to combine effective medicines."

It’s also possible, indeed probable, that antiangiogenic drugs will be used to prevent cancer from ever developing, just as aspirin is taken to prevent heart attacks.

Bypassing the tumor to attack its roots? Avoiding the side effects and disfigurement of surgery? No wonder National Cancer Institute Director Dr. Richard Klausner has called antiangiogenesis "the single most exciting thing on the horizon."