Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

Biotechnology versus Bioterror

February 20, 2003 · Michael Fumento · Scripps Howard News Service · Biotech"When spring comes, a young man’s fancy turns lightly to thoughts of love," wrote Tennyson. But with Iraq’s brutal dictatorship caught in a death grip and seeking any way to strike back, this spring has brought thoughts of bioterrorism.

The best way to deal with terrorists is at the root: hunt them down and kill them. Nevertheless, we must also build a multi-layered defense against deadly microbial attacks. Biotech companies across the country are doing just that: developing an incredible array of vaccines, drugs, and detection devices.

It’s a daunting task. The CDC has compiled a list of 30 biological threats. But since the September 11 attacks, the number of biotech companies focused on this area has grown from just over a score to as many as 100, according to the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) in Washington, D.C.

This massive effort will be encouraged by "Project BioShield," which President Bush announced in his January State of the Union Address. It requests, in addition to $2.6 billion already allotted for biodefense protection, an additional $6 billion in spending over the next ten years.

Although most smallpox victims survive, they remain scarred for life.

Already we have vaccines that protect against some potential bioterror agents such as smallpox and anthrax. But major challenges include providing protection against other possible bioterror pathogens and shortening the time needed to establish immunity.

For example, the current anthrax vaccination requires six injections spread over 18 months to provide complete protection. But a gene-spliced vaccine under development by DVC of Reston, Va. would confer immunity with fewer injections, although that number has yet to be determined.

The third generation will be an oral vaccine from Avant Immunotherapeutics of Needham, Mass. It splices genes from anthrax and plague into a cholera vaccine already in advanced testing, thereby protecting against all three diseases. Theoretically, says Avant CEO Una Ryan, "We could keep adding in genes from other microbes that would protect against an even wider variety of bioterrorist threats."

But what about persons already struck down by a bioterror weapon? Some drugs already exist (such as the newer Cipro, but also older antibiotics) that may save many lives. Ultimately, though, we want individual drugs that will defeat a broad spectrum of pathogens. That’s why the Ibis Therapeutics division of Isis Pharmaceuticals has been working since 1997 to develop a single weapon to kill every type of bacterium.

"You do that by looking for various common denominators that exist among all types of bacteria and making those your drug targets," says David Ecker, president of the Ibis division in Carlsbad, California. "Our expertise is in RNA."

RNA is a chemical structure in cells that helps translate the genetic information of DNA in order to make new proteins. "We’re developing chemicals that bind to bacterial RNA and prevent that translating," he told me. All bacteria in the body – even that genetically modified to resist current antibiotics – would be zapped. (Yes, that would also destroy beneficial microbes, but many antibiotics already do that. The good bacteria usually grow back quickly.)

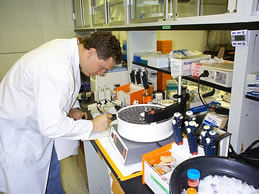

It’s not as impressive as a B-1 bomber, but labs like this are also fighting the war on terror.

Moreover, such a drug would even help protect against viral bioterror agents because often it’s not the virus that actually kills but rather bacterial secondary infections. Ibis is currently testing variations of its therapy in mice.

Devices for rapid detection of airborne and waterborne pathogens are also critical, and many such already exist. Called "biosensors," these devices usually use proteins to detect chemicals or other biological molecules. But the race is on to make them more portable, more accurate, and capable of detecting a broader spectrum of microbes.

One of the most promising is the EchoSensor from Echo Technologies of Alexandria, Virginia. It can detect and distinguish among groups of biological agents such as bacteria and bacterial spores, fungal spores, and toxins as well as measure the level of contamination. The detectors would be built into handheld devices or even worn as a "badge."

Echo Technologies says the detection system reduces the time required for biological analysis from hours or even days to only minutes.

EchoSensor will probably be widely distributed among law enforcement and public health agencies, as well as public and private entities concerned not with bioterror but good old-fashioned pollution. It should be available within a year.

There’s no cause for panic over the threat of bioterror. But the less prepared we are, the more likely an attack. So it’s good to know that while our heroes in camouflage are bringing the war to the enemy, we also have heroes in white lab coats fighting to prevent the enemy from bringing the war to us.