Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

And Now For The Real Economic Crisis

August 05, 2011 · Michael Fumento · EconomyIn ending the immediate debt-ceiling crisis this week, Congress did nothing to address the United States’ long-term economic crisis. Its latest spending cuts won’t even cover the debt we’ll rack up this year.

The long-term crisis is threefold: We’ve amassed a huge debt; we’re running a massive annual deficit; and the economy has essentially flatlined: It grew at an annualized rate of less than 1 percent in the first half of the year, and but for population growth it probably would have shrunk slightly.

All three have roots in an almost pathological American positivism - the very same that led to both the dot-com and housing bubbles. We seem to believe that "American exceptionalism" exempts us from the rules of economics.

Decision time, folks. Will we embrace painful realism and do what’s necessary to survive? Or will we simply close our eyes and hope the monster doesn’t see us? The monster, incidentally, is default followed by Great Depression II.

Just half a year ago, the Federal Reserve predicted that gross domestic product would grow by as much as 5 percent this year; the White House forecast 2.7 percent; and the Congressional Budget Office 3.1 percent.

What went wrong? Nothing. That’s the point. Everything we’re seeing now is the result of easily explainable economic trends that began decades ago - trends we ignored and continue to pretend are merely "cyclic," using terms like "soft patch."

The White House forecast for this year was relatively sober compared with its projection of more than 4 percent annual growth over the next decade. We haven’t seen that since the 1960s, and even the "Roaring ’20s" roared at an average of just 4.2 percent annually (before the bottom fell out).

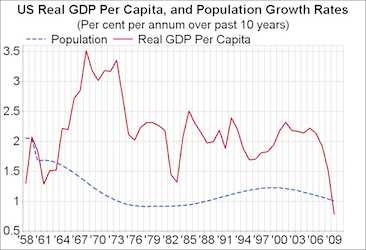

From 1950 to 2000, the economy expanded at an average of 3.5 percent a year. But as economies mature, growth normally declines and levels off. U.S. growth peaked back in the 1960s and now ranks just 129th out of 216 countries.

No laws of economics, however, could have predicted America’s failure to meet the challenge of globalization. We’ve run foreign trade deficits for 35 years straight and now import about a third more than we export.

It’s debatable what role foreign trade plays in GDP growth; but it’s symptomatic of a greater problem. Germany and Canada also have mature economies, yet Germany is the world’s second largest exporter and Canada, with one small dip, has had decades of positive trade balances. Both of their economies are growing at three to four times our rate.

Indeed, it’s been calculated that the U.S. economy would have been shrinking over the last three decades but for two factors. One was a sharp increase in borrowing around 1980 - a little while before either President Obama or George W. Bush took office. Like Popeye’s friend Wimpy, we offered to "Gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today" and hoped Tuesday would never come.

Now we’re addicted. About half our government spending is fueled by borrowing, and that spending accounts for a fourth of GDP. Without borrowing, then, our GDP would drop 12 percent or more - well into depression range.

The other reason the economy has continued to grow is simply that our population has. The British macroeconomist Gavyn Davies observed in the Financial Times that "once we adjust for population growth," U.S. economic expansion was "stuck fairly close to 2 percent" from the mid-1970s to the mid-2000s.

Since then, Davies said, "something has clearly gone very wrong." From 2000 until the 2008 recession, the economy expanded at a miserly annual rate of 2.39 percent, and merely 1.1 percent after adjusting for inflation - despite a massive infusion of wealth from the housing bubble.

So, with an economy falling behind the pace of an arthritic snail, and in the full knowledge that we must drastically cut the borrowing that’s been propping it up, the White House told us a few months ago to prepare for one of the greatest economic booms in modern American history. Sure, part of that projection was politics. But part of it was pure, scary self-delusion.

Unfortunately, the administration’s fiscal fantasy makes the Congressional Budget Office’s projection of 2.85 percent annual growth over the next decade look reasonable, which it isn’t. But even if it were, deficit spending in the coming decade would increase by a stunning $9.5 trillion. If the economy ends up growing by only 2 percent a year, and revenues shrink accordingly, deficit spending will balloon to $20 trillion.

The U.S. economic policy of both pretending things aren't nearly as bad as they are and pretending that economic laws don't apply to us portends disaster.

To address this, before the debt-ceiling negotiations, the Obama administration proposed to cut spending by at most $4 trillion over 12 years. Rep. Paul Ryan’s plan would ostensibly reduce it by $4.4 trillion over a decade. You don’t need a supercomputer to see the problem. As the Financial Times’ Davies bluntly stated, "There is no credible plan in place for reducing this deficit in the short, medium, or long term."

Our creditors are also capable of self-delusion. Indeed, half of our public debt is held not by foreign countries, but by Americans. But with prodding from credit rating agencies, it will eventually sink in that the United States is the next Greece or Portugal, though with no European Union to bail us out. [Note: The evening this article appeared, Standard & Poor’s lowered the U.S. credit rating for the first time in history.] When the leader of a huge nation (Russia) that has invested half its savings in dollars labels you an economic "parasite," take notice. We may believe America enjoys some sort of magical or God-given "exceptionalism," but others are getting scared.

That could mean that the United States, like several European nations, has to dramatically increase the interest it pays on debt. Or U.S. creditors could start pulling out as fast as possible in what one international organization called "a sudden rush for the exits."

Washington has very little time left to come up with a response that must be considered a failure if it doesn’t cause Americans great pain. Revisiting the Great Depression would be far more painful.