Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

A Peace Prize for Aiding and Abetting a Drug Cartel

October 17, 2016 · Michael Fumento · The American ConservativeThere have been some curious recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize such as terrorist Yasser Arafat. Yet somehow it’s managed to lower its prestige even further with its award to Colombian President John Manuel Santos for his efforts in negotiating a “peace accord” to end “a half-century war with communist guerrillas.” As educated Colombians seem to know with their rejection of the treaty (albeit narrowly) there are no “communist guerrillas” nor is there any real war. Rather, Santos made a cushy treaty with a narco-terrorist group that in terms of sheer numbers makes Pablo Escobar’s Medellín Cartel look like a Boy Scout Troop. We’ll see why.

The official announcement makes it appear the committee was both seeking to reward Santos for brokering the agreement, to encourage Colombian voters to rethink their referendum vote, or both. Yet the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) long ago ceased being either communist or guerrillas. At one time, they and other rebel groups were ideologically driven and sought to violently overthrow the government. Today, however, their ideology is “plata” (money).

Which brings us to what this treaty is really about—for both sides.

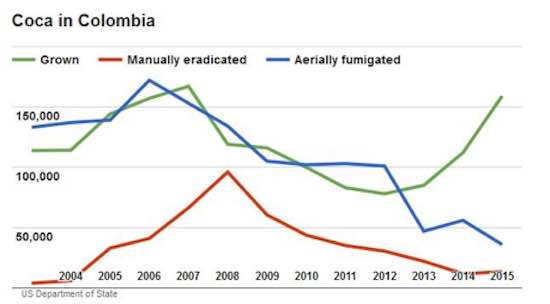

Although the FARC only controls a small percentage of Colombian territory, that area accounts for about 70 percent of the nation’s coca cultivation. Colombia as a whole produces about half of the world’s cocaine supply, including over 90 percent of that used in North America. (A small amount is used domestically, as both cocaine and marijuana for personal use were declared legal in 2012 after Santos’ predecessor had them outlawed.) Far from successfully reducing this, has seen an incredible doubling in the planted coca crop area in just the last two years, according to the latest Colombia Coca Survey—jointly produced by UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the Colombian government itself. (See chart.)

Much of this increase is directly attributable to Santos ending aerial spraying last year, which is vastly more effective than sending troops into areas guarded by “narcotrafficantes” and their horrible land mines. And safer. I lived in Colombia for four years until last December: You see a lot of missing legs there, virtually always on men. “Las minas de las FARC?” I would ask. “Si, se√±or.” But Santos insists aerial spraying will not resume, despite the country’s chief prosecutor having recently called for doing so.

Why not spray? Santos cited potential health effects of the herbicide, glyphosate (ubiquitously used in the U.S. under the commercial name Roundup.) But just in August, New Zealand’s EPA Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) declared the herbicide should not be classified as a mutagen or carcinogen based on years of studies reviewed by a host of authorities worldwide: the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the European Food Safety Authority, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the World Health Organization, and the US EPA. Santos just wants no spraying.

The likely reason: Both drug exports and the money received for reducing them are extremely valuable sources of revenue for the country—and quite possibly for Santos, other high-level Colombian politicians, and others with any interaction with drug trafficking. Which isn’t a lot of people, but rather a lot of important ones.

OTHER THINGS GO BETTER WITH COKE

Nor is cocaine Colombia’s only drug export by any means. Heroin exports are increasing rapidly.

A 2015 report from UNODC shows opium poppy cultivation in Colombia rose by almost 30 percent between 2013 and 2014, to the highest level observed since 2008. “Colombian organizations appear to have shifted their focus from low-level distribution to large-scale production,” notes the Insight Crime Foundation. “The United States continues to consider Colombia the primary source of heroin” in the U.S., according to a 2013 UNODC report, (although Mexico may be moving ahead). The FARC is believed to control a major portion of opiate production.

Now add in that last year Santos legalized growing “medical and scientific” marijuana—which, of course, will facilitate all marijuana growing. (One marijuana plant looks just like the next: Authorities have no idea which ones will be used, ahem, medically and scientifically.) Now its legislators are considering doing the same with coca; which would put 100 percent of control efforts onto the most inefficient means of control, interdiction. Put it all together and you can see how the money piles up.

Surely the writer isn’t insinuating that Santos wants the drug trade to continue! Oh, surely he is!

In part, it’s a major source of badly-needed export revenue for the country. While underdeveloped nations are usually net exporters, Colombia has a negative balance of trade. Legal exports were only US$35.7 billion in 2015. That’s down 37.3 percent since 2011 because the exports comprise mostly of coal and oil. That’s how important that $10 billion in cocaine sales alone is.

Yet it’s also a hefty source of foreign aid. By emphasizing worthless information, like hyping individual drug interceptions, the Santos government keeps U.S. dollars and material support coming in under “Plan Colombia”—over $9 billion since 2000. Although lauded by both Santos and Secretary of State John Kerry as a tremendous success, by the original standards it’s been a total failure. American taxpayers are literally paying Colombia to grow more drugs.

TREATY REJECTION AS REJECTION OF SANTOS

I doubt the Colombian people know many of these details beyond the realization that the FARC is not an ideological guerrilla group but rather the world’s biggest drug cartel. Colombians are not avid readers, and the new treaty (a 297-page document) would be rather much even if they were. Many probably wrongly thought it contained a general amnesty to people who have wreaked so much havoc on their nation for 52 years. I personally knew a woman who said the FARC killed her parents and the local leader took her as a rape mistress at age 13.

They also know that Santos is corrupt and untrustworthy even by the sad standards to which they’ve become accustomed. And that means they know more than the folks who hand out Nobels.

Corruption in Norway, where the Peace Prize committee sits, is almost the lowest in the world and people tend to project their values onto others. Not smart. Colombia ranks in the middle, tied with Liberia. A late August Gallup poll showed that 85 percent of urban Colombians believe that corruption in the country is getting worse. (That’s like denizens of hell believing it’s getting hotter.) But the general rule is that the more prevalent a problem, the more it becomes like background noise and is ignored. Colombians just assume their elected officials are on the take. That most definitely includes bribes from the narco-traffickers, with those refusing payoffs risking to have their shipments seized.

Which isn’t to say you can’t push even Colombians too far.

They don’t just distrust Santos; they loathe him, to the point where (as a recent Colombian newspaper headline put it), “Santos’ Approval Rating Gradually Approaching Zero Percent.” (Actually, it’s 13 percent, but down from a formerly sky-high 75 percent when he took office six years ago.) Surely in part he’s being blamed (unfairly) for the fallout from low oil and coal prices. But there’s more educated Colombians know about him and the situation with the FARC that hasn’t reached ears in Oslo or other places where “expert analysts” have been utterly dumbfounded by the “rejection of a peace accord that would end a half century of war.” To the extent there’s been a decline in fighting in Colombia, it’s primarily from the tremendous success of Santo’s predecessor, Álvaro Uribe, who led opposition to the so-called peace accord.

During his two terms from 2002-2010 Uribe devastated the FARC, whose numbers fell from about 20,000 members to 8,000. And partly it’s been the offshoring of cartel violence to Mexico. The Mexican homicide rate soared from 16.6 per 100,000 in 1995 to 23.5 in 2012, because sending the drugs to Mexico first is much safer than shipping them all the way from South America to U.S. and Canadian ports of entry.

Now the Mexican cartels are expanding to both the U.S. and Canada, and so we can expect a rise in gang-related violence from that. But remember folks, Mexico doesn’t grow coca. The problem is Colombia.

Educated Colombians also know the FARC will see no purpose in laying down its weapons and encouraging peasants to change crops from white gold to something mundane like coffee—the price of which has greatly fallen in recent years. And if nothing else it’s in competition with other armed cartels. Further, only a tiny number of Colombians directly gains anything from the drug trade—the growers, the narco-traffickers, and corrupt government officials with their take. Yes the country, especially drug hub Medellín, is experiencing a building boom fueled in great part by drugs. (As was earlier the case in Miami.) But nobody likes to admit that.

The arrogance and ignorance of the Nobel Committee is pitiful. Maybe next year they can award it to somebody more deserving. Vladimir Putin will be anxiously waiting by his phone.